Table of Contents

Abstract

Problem

Traditional assessment metrics (e.g., GPA, final exams, quizzes) do not adequately capture the breadth of knowledge and skillsets required to be successful in clinical settings. As students move from classroom-based curriculum to a more hands-on clinical curriculum, assessment methods and tools need to be developed to assess a student’s preparedness to enter these spaces. Specifically, tools are needed to assess student non-cognitive attributes (e.g., teamwork, professionalism), which are required to be successful in clinical spaces.

Approach

Faculty members representing the programs of Medicine, Physician Assistant, Dentistry, Nursing, Occupational/Physical Therapy, and Pharmacy formed a working group to discuss the necessary non-cognitive attributes required to be successful in the clinical portion of their respective curriculum. The working group developed scenarios and response items to incorporate into a Situational Judgement Test called the Transitions Situational Judgement Test (T-SJT) aimed at assessing student’s readiness to enter the clinical portion of their education.

Outcomes

The Transitions Situational Judgement Test (T-SJT) was administered to 59 students representing two different health professional programs. There was no significant difference in T-SJT scores based on program, or gender. The test had promising reliability score with a Cronbach’s alpha of .80.

Next Steps

Researchers are currently enrolling additional students to participate in a second wave of data collection of the T-SJT test to increase the sample size. Further analysis of the data will be conducted to ensure the reliability of the T-SJT and to assess generalizability (differences in scores by discipline) across programs. Additionally, researchers will correlate admissions assessment data (e.g., admissions SJT score, MCAT, GPA, MMI score) with the participants T-SJT score to assess the T-SJT validity and better understand how this assessment differs from traditional assessment metrics.

Problem

As many health professional programs move to more holistic admissions, they have been increasingly developing and utilizing Situational Judgement Tests (SJT’s) to assess potential applicants.1,2 SJT’s have been primarily used to assess an applicant’s non-cognitive attributes, such as professionalism and communication skills.1,2 While SJT’s provide value as a component of a holistic admissions process, SJT’s might also provide a unique tool that can be used beyond admissions due to their ability to assess attributes and traits that are necessary in applicants beyond admissions.3

Traditional cognitive metrics, including performance on pre-admissions exams (such as the MCAT in medicine) and GPA, assess and measure specific content-knowledge related to the applicant’s ability to perform well in a classroom setting.2 However, these tools fail to capture important underlying non-cognitive traits such as teamwork, professionalism, and communication skills, which are required to be successful in health science careers.1 As health professional programs implement SJT’s into their holistic admissions approach to assess non-cognitive attributes, SJT’s should also be implemented and utilized where appropriate throughout the rest of the curriculum as these traits and characteristics are vital for student success as they progress through their education.3

Upon completion of classroom-based learning prior to moving into clinical-based learning settings, students across the health profession programs are required to demonstrate on cognitive assessments that they have met curriculum objectives focused on knowledge acquisition to ensure they “can apply important concepts of the sciences basic to the practice of [providing care]” (USMLE Website). Following this logic, the authors believe that SJT’s should also be used in this transition period to assess students’ ongoing development of non-cognitive traits, and hence their readiness to be act appropriately in socially complex patient-care settings. In pharmacy education, for example, programs are required by their accrediting body to explicitly measure students’ readiness for applied learning experiences prior to beginning those experiences.

Furthermore, we believe that student development of non-cognitive traits is not specific to a given profession. Traits such as professionalism, communication, and teamwork, are necessary for all students to be successful learners, regardless of their respective fields. Hence, we hypothesized that we could develop a common SJT to assesses these traits in students from multiple health professions programs prior to students’ transition from classroom-based to clinical-based learning contexts.

SJT’s are composed of narrative scenarios and response items meant to assess the examinees’ response in areas covering multiple underlying constructs (e.g., communication, teamwork, empathy). Examinees are presented scenarios and different item responses to address each scenario. They must then either rank or evaluate each response as it pertains to the scenario. This is often in the form of a Likert scale where items are ranked independently based on appropriateness or effectiveness of the items in response to the scenario. However, different scoring and structural changes to items (e.g., rank order, rank independently, select all that apply) can be made to the SJT’s and add to the dynamic nature of the SJT and ability to assess different factors.

In this paper, we describe the development and pilot use of a health professions transition SJT at the University Utah. We designed our SJT to measure a subset of students’ non-cognitive traits, which are considered as indicators of their readiness to learn in patient-care settings.

Approach

Faculty members from across health science programs at the University of Utah met to discuss SJT’s and how and if they were being utilized in their respective programs. This included representation from programs of Pharmacy, Dentistry, Medicine, Occupational/Physical Therapy, Nursing, and Physician Assistants. Faculty experience ranged from having no experience at all to serving as subject matter experts in SJT development. These faculty formed a working group which met over several months to discuss in detail how to develop a clinically oriented SJT. The group reviewed different characteristics and traits that are vital for students in a clinical setting to exhibit and the types of challenging clinical scenarios they are likely to face.

By reviewing the literature and discussing traits sought after in their respective health science program, the group identified 5 categories of traits that students should exhibit to be successful in clinical settings. These categories helped guide the development of scenarios and item responses:

- Self-directed learning and personal accountability

- Compassion

- Professionalism

- Teamwork

- Service Orientation

In addition to using these trait categories to develop clinical scenarios and responses, the same group was given a large pool of ethically challenging clinical situations written by 4th year medical students. These students were part of an admissions elective that included a requirement to submit descriptions of challenging clinical scenarios, based on their personal experiences and which could inform assessments of non-cognitive traits. Faculty were asked to review these scenarios and tailor them to be generalizable across health professions programs. Scenarios and items were then reviewed by individual faculty members in the working group and discussed in the large group meetings. Altogether, the group developed 31 different scenarios with 3-5 responses for each scenario which we compiled into our Transitions Situational Judgement Test (T-SJT). We used a 5-point Likert response scale: 1=Very Inappropriate, 2 Mostly Inappropriate, 3-Neutral, 4-Mostly Appropriate, 5-Very Appropriate . We include a sample scenario and responses in Appendix 1.

To facilitate data collection, we implemented the T-SJT using Qualtrics (an online survey platform). For quality control, we first administered the T-SJT to members of the working group and other health science faculty. We used their responses to identify problematic items (e.g., items that multiple faculty agreed needed rewording) and help develop and validate an answer key. Additionally, we asked participants to provide feedback about revisions needed to add clarity and avoid confusion about specific scenarios and response items. We used all of these data to edit the T-SJT and prepare an improved version to administer to students.

We invited students from different health professions programs to take the T-SJT at their convenience. We sent emails to students with details about the T-SJT and a link to the test via each program’s list serve. Students were offered $25 in exchange for completion of the T-SJT.

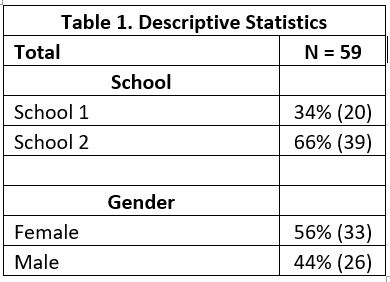

Ultimately, 59 students representing two different programs took the test (See table 1).

Using the answer key based on the average response of working group members, we calculated examinee scores by comparing each examinee response for each item to the working group average for that item. Hence the closer the examinee response was to the working group average, the greater the number of points the examinee earned for the item. We then summed points earned on individual items together to create a final combined score across for the entire test. We reported this total test score as a percentage of maximum possible points.

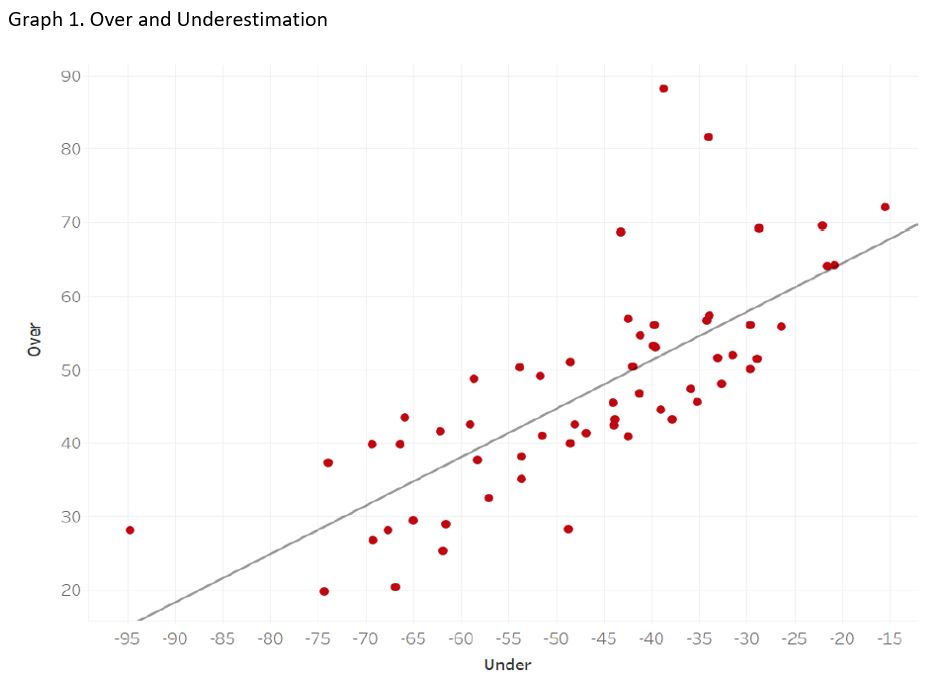

Because examinee response for each item could be greater than or less than the working group average, we also considered the examinee’s tendency to overstate the appropriateness of response (choosing a response higher than the working group average) and to understand the appropriateness of response (choosing a response lower than the working group average). We represented these tendencies as the sum of all items that were over-stated and the sum of all items that were under-stated. We hypothesized that identifying students’ tendency to over or under state the appropriateness of given responses would add important insight to examinees non-cognitive traits and allow for more specific feedback about areas of concern.

Outcomes

The average score on the test was 93.5. and did not vary significantly by program or gender. School 1’s average was a 94.9 and school 2’s average was 92.8. Females averaged a 93.6 and males average a 93.0. We calculated a Cronbach’s alpha obtained a score of .80, indicating the test was reliable. See table 2 for details of analysis.

Graph 1 shows participants tendency to overstate and understate appropriateness of responses. Each dot on the scatter plot shows a students score. Dots above the line show students who tend to overestimate appropriateness of responses, while dots below the line show students who tend to underestimate appropriateness of responses.

Next Steps

Findings indicate researchers created a reliable SJT test, irrespective of program or gender. This is promising as it suggests the generalizability of the test and indicates it can be used to assess students across different health professions programs Additionally, we plan to assess the validity of the test by correlating participant scores on the T-SJT with other admissions assessments designed to assess the same non-cognitive traits. This includes correlating participants T-SJT scores with their admission SJT score, multiple mini-interview scores, structured video interviews score, MCAT score, and GPA.

We believe that the graph showing examinees’ tendency to over- and under-state appropriateness of responses also shows promising data. We expect to use such data to identify students who may be outliers when it comes to over or understating appropriateness of responses and provide feedback to these students before their transition to a clinical learning context. We anticipate that this will provide actionable information to the student and be a useful learning opportunity for them to reflect on.

We are also looking to use the T-SJT in new and innovative ways. This includes using T-SJT scenarios and item responses as a discussion tool for classroom lectures and workshops. As opportunities present themselves for the utilization of the T-SJT in these ways, we will conduct qualitative analysis of how this tool facilitates discussion and learning for participants.

References

- Fiona Patterson, Lara Zibarras & Vicki Ashworth (2016) Situational judgement tests in medical education and training: Research, theory and practice: AMEE Guide No. 100, Medical Teacher, 38:1, 3-17, DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1072619

- Lievens, F. (2013) ‘Adjusting medical school admission: Assessing interpersonal skills using situational judgement tests’, Medical Education, 47(2), pp. 182–189. doi: 10.1111/medu.12089.

- Cousans, F. et al. (2017) ‘Evaluating the complementary roles of an SJT and academic assessment for entry into clinical practice’, Advances in Health Sciences Education. Springer Netherlands, 22(2), pp. 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9755-4.

Return to Table of Contents:

Development of a Situational Judgement Test to Assess Student Clinical Preparedness by Taylor Dean, MS, Boyd F. Richards, PhD, Brian Good, MD, BCh, BAO, Jawaria Khan, MD, FAAP & Krystal Moorman, PharmD