Table of Contents

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study is to use consensus methodology involving various educators to identify key curricular items about systemic lupus erythematosus that medical students should learn about during undergraduate medical education.

Methods: 86 faculty and housestaff members were invited to participate in a 3 step Delphi consensus process. Step 1 involved reviewing the current items in the curriculum and requesting suggestions for additional items. In step 2, each participant rated every item’s importance to be included in the medical school curriculum using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all important; 5 = extremely important). In step 3, participants were given the group’s mean and mode rating for each item, reminded of their own initial rating, and asked to make a final 5-point rating. After the final step, items rated ³4 (“very important” or “extremely important”) by at least 80% of participants were retained.

Results: 44 participants accepted the invitation to join our consensus project (51%); 31 participants completed all steps (37% of invited members, 70% of accepted participants).

In step 1, 61 items were added as suggestions to the curriculum leading to a total of 82 items to be rated. The consensus process eliminated 50 items, leaving 32 in the final list of identified important key teaching elements for lupus.

Conclusion: Using a systematic consensus exercise, a diverse group of educators participating in the lupus consensus project identified key teaching items to prioritize during medical school education.

Introduction

Creating a curriculum that adequately teaches systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be overwhelming for both the medical student and the teacher. Systemic lupus, or simply “lupus” for this publication, is a complex multi-organ disease entity with multiple clinical and laboratory features as displayed in the 2019 EULAR/ACR Classification Criteria(1). When learning about lupus, students can feel confused by this complex disease given the multiple facets involved. Students grade their confidence in knowledge of lupus as neutral as determined by Mok and colleagues(2), but these authors also demonstrate that a large proportion of students use external curricular resources such as the internet and materials provided by professional societies. Kerezoudis, et al., cites in his study that students believe that lupus represents a “model autoimmune systemic disease that can provide the opportunity for deeper understanding of other systemic autoimmune diseases” (3). Medical students also perceive lupus as life-threatening, more burdensome, and having worse consequences even compared to lupus patients given the possible complications (4).

Because SLE is recognized as a rheumatologic disease, it is reasonable that the responsibility for undergraduate medical curriculum in lupus is primarily entrusted to rheumatology faculty. However, lupus spans multiple complex systems, thus medical educators outside of rheumatology also hold stake in determining what elements of lupus are appropriate for undergraduate medical education (UME). Although rheumatology faculty may be identified as curriculum leaders for SLE, faculty in other disciplines relevant to lupus (e.g., nephrology, pulmonology, cardiology, dermatology, etc.) may have varying—even conflicting—opinions regarding specific content or learning objectives. Students also recognize that SLE needs a multidisciplinary approach (5). These factors add further complexity to curricular design. Recent literature stresses the importance of teaching epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, management, and treatment but offers little guidance in determining what the essential teaching items should be in UME (2,3).

The aim of this study was to use consensus methodology involving various stakeholders to identify key lupus curricular items that medical students should learn during their four year education. The identification of specific key items will help streamline medical education for lupus and uniformly prepare graduating students to potentially recognize key aspects of this complex disease.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment

Key stakeholders were identified through review of all faculty engaged across the range of rheumatology educational experiences at the University of Utah School of Medicine (UUSOM). This included all adult and pediatric rheumatology faculty and fellows, internal medicine chief residents, all content experts in UME, members of the curriculum evaluation committee, all deans, internal medicine clerkship directors, and preclinical curriculum course directors. Content experts included PhD, MD, and DO faculty who were assigned by UUSOM to be designated advisors in the specific areas of interest. There were identified content experts in all subjects including: Gross Anatomy, Allergy and Immunology, Cardiology, Dermatology, Community Engaged Learning, Embryology, Endocrine, Genetics, Gastroenterology, Histology, Hematology/oncology, Human Behavior, Infectious disease, Metabolism and Nutrition, Pathology, Pulmonary, Rheumatology, and Renal (https://medicine.utah.edu/students/programs/md/curriculum/core-educator-program/domain-experts.php).

A total of 86 faculty and housestaff members from the UUSOM were identified as stakeholders and invited by email to participate in the consensus process.

Consensus Process

Initial review of the four year UME curriculum at UUSOM identified 21 content items currently included in lupus instruction across all subject areas. This initial review was conducted by the designated rheumatology content expert (JKT) for UUSOM.

A 3-step Delphi consensus process was conducted. Step 1 involved accepting invited participants to review these 21 items in the current curriculum and suggest additional items. In step 2, each participant rated each item’s importance to be included in the medical school curriculum using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all important; 5 = extremely important); suggested items from step 1 were also included. In the 3rd step, participants were given the group’s mean and mode rating for each item from step 2, reminded of their own initial rating, and were asked to make a final rating for each item. Individual responses to each step remained anonymous. All communication including solicitation and the rating procedures were performed by email.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed responses to each survey item by calculating the mean, mode, and standard deviation. After the final step, individual items rated ³4 (“very important” or “extremely important”) by at least 80% of participants were retained; these identified items defined the set of lupus curricular elements representing the consensus of the group. This study was deemed IRB exempt.

Results

44 participants accepted the invitation to join our consensus project (51% of total invited members). 31 participants completed all steps of the consensus project (37% of invited members, 70% of participants who accepted). The majority were rheumatologists (16, 52% of total), 4 participants were from internal medicine, and 11 participants were medical school educators (6 of these medical educators also had internal medicine backgrounds). Three medical school deans participated. Participants also included designated content experts in Gross Anatomy, Community Engaged Learning, Embryology, Endocrine, Histology, Hematology/oncology, Human Behavior, Metabolism and Nutrition, Pathology, Pulmonary, Physiology, and Rheumatology.

In step 1, 61 items were added as suggestions to the curriculum leading to a total of 82 items to be rated and reviewed (see Supplement 1) . Additional items included knowledge about innate and adaptive immunity, understanding cardiac manifestations, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Other additions included learning about social determinants of health and how this impacts diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

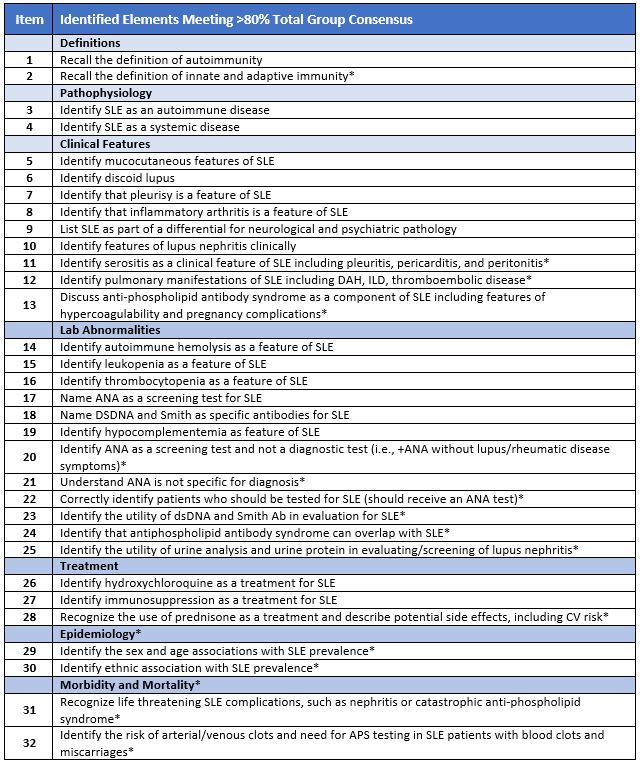

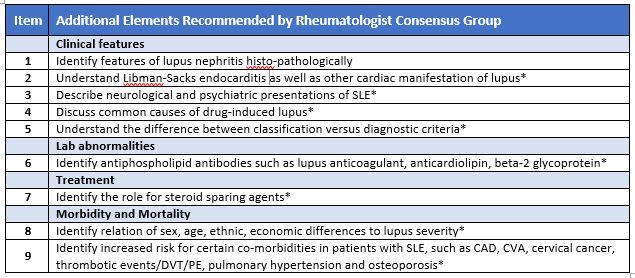

The consensus process eliminated 50 items out of the total 82 items. Thirty-two items remained in the final list of identified important key teaching elements for lupus (see Table 1). In a post-hoc analysis of ratings provided by rheumatologists, 9 additional elements were identified though these did not meet total group consensus (see Table 2). Seventeen of the original twenty-one items remained after completion of this study.

Discussion

Through consensus methodology, this study identified 32 key lupus items to prioritize in the UME curriculum. Multiple original items were eliminated or modified during this process including specific items detailing pathophysiology such as specific type identification of hypersensitivity reaction and pathology identification of lupus nephritis. These items may be too specific and granular for medical student education. Multiple items were added, including discussion of epidemiology and risks for increased morbidity and mortality. Interestingly, nine additional items were recommended by rheumatologist in post-hoc analysis. These items included more detailed knowledge in regards to clinical features, lab abnormalities, and need for treatment other than steroids (or steroid sparing agents). Rheumatologists likely placed higher value on medical student awareness of variable lupus phenotypes and range of options for management.

Recent rheumatology publications supports that early recognition of lupus symptoms leads to earlier diagnosis and potentially improved outcomes. Kernder, et al. illustrated that a delayed diagnosis of lupus is associated with worse outcomes (6).Oglesby, et al. demonstrates that “patients diagnosed with SLE sooner may experience lower flare rates, less healthcare utilization, and lower costs” (7). Thus, teaching graduating medical students the varied clinical manifestations and lab abnormalities may lead to shorter time to diagnosis and early initiation of steroid sparing agents. This, in part, will lead to improved outcomes for lupus patients.

UME is undergoing curriculum reform with increasing desire for interdisciplinary overlap in education. Lupus is a prototype condition that requires layered and overlapping knowledge of basic science, clinical immunology, and pathology (3). Engaging stakeholders from various disciplines in this systematic consensus process facilitates integration of many perspectives into a more comprehensive curriculum. Curriculum integration creates new collaborations within the community of teachers at an academic center and more robust and impactful educational experiences for learners. Demonstration of a multidisciplinary fourth year elective called “Understanding Lupus” shows success in focusing on lupus as a chronic disease process that ties multiple interdisciplinary objectives together with basic science (5). This same concept may be applied in development of teaching sessions at the start of medical education. This can create a framework for pre-clinical curriculum with utilization of these key items as building blocks.

Limitations of this study include conduction of the consensus process with stakeholders at a single academic center. Another limitation includes the low total percentage of invited participants who completed all three steps of the project, at 37%. This study did not include persons not involved in medical education, thus not capturing data from rheumatologists in non-academic centers.

The next step involves using these key items to develop learning objectives. These objectives then can be used as a roadmap for curriculum design to educate students about this complex disease process.

References

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, Brinks R, Mosca M, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Mok M, Lo Y, and Lau C. A Needs Assessment and Review Curriculum of Content of Teaching on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (abstract). Arthritis Rheumatology, 2013.

- Kerezoudis P, Lontos K, Apostolopoulou A, Christofides A, Banos A, Leventis D.,,et al. (2016). Lupus in medical education: student awareness of basic, clinical, and interdisciplinary aspects of complex diseases. Journal of Contemporary Medical Education 2016; 4: 97-106.

- Nowicka-Sauer K, Pietrzykowska M, Banaszkiewicz D, Hajduk A, Czuszyńska Z, Smoleńska Ż. How do patients and doctors-to-be perceive systemic lupus erythematosus? Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:725-9.

- Nambudiri VE, Newman LR, Haynes HA, Schur P, Vleugels RA. Creation of a novel, interdisciplinary, multisite clerkship: “understanding lupus”. Acad Med. 2014;89:404-9.

- Kernder A, Richter JG, Fischer-Betz R, Winkler-Rohlfing B, Brinks R, Aringer M, et al. Delayed diagnosis adversely affects outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus: Cross sectional analysis of the LuLa cohort. Lupus. 2021;30:431-438.

- Oglesby A, Korves C, Laliberté F, Dennis G, Rao, S, Suthoff E, et al. Impact of early versus late systemic lupus erythematosus diagnosis on clinical and economic outcomes. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12:179-190.

Return to Table of Contents: 2022 Journal of the Academy of Health Sciences: A Pre-Print Repository

Identifying Key Items in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus for Undergraduate Medical Education: A Consensus Study by Julie K. Thomas, MD, Michael Battistone, MD & Andrea Barker, MPAS, PA-C