Table of Contents

Abstract

Introduction

While point of care ultrasound (POCUS) education has been demonstrated as a need in pediatric residency programs from a resident and program director perspective, few pediatric residency programs integrate POCUS education into their curricula.

Methods

We designed and implemented a two week-long pediatric elective designed to increase resident confidence in cardiac, lung, and abdominal POCUS examinations. We evaluated residents’ confidence using a Likert scale survey before the elective, after the elective, and at least 18 months after completion of the elective.

Results

Globally, resident confidence across all POCUS domains increased significantly and persisted for at least eighteen months after elective completion. Qualitative analysis of course feedback revealed resident perception of strength in POCUS training with opportunities for expanding the elective.

Discussion

This study of a novel POCUS curriculum in a pediatric residency program demonstrates increased confidence with POCUS skills which persisted post-residency graduation. The described curriculum could serve as a model for other programs and institutions seeking to incorporate an efficient method of teaching this important skill.

Introduction

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a growing field in medical management and education, and several specialties including emergency medicine, internal medicine, and general surgery have integrated POCUS into resident training. [1-4]. POCUS uses no radiation, can be done at the bedside, and is generally well tolerated, making it an ideal imaging modality for pediatrics. However, in pediatric residency programs, utilization varies widely between institutions [5]. Despite strong evidence displaying POCUS’s benefit in routine conditions, as well as a belief among a majority of surveyed residency programs that residents should be trained in POCUS, POCUS education has had minimal implementation at most pediatric residency programs of emergency departments and ICUs. [6-7]. Among the many utilities for POCUS in pediatric patients, strong evidence exists for its use to rule in intra-abdominal injury (IAI), to diagnose pneumonia and pneumothorax, and to identify patients with bronchiolitis with severe airway disease and likely prolonged oxygen requirements, all with equivalency to (and in some cases superiority over) more traditional imaging modalities [8-12].

The AAP has acknowledged POCUS’s utility, specifically as a useful method of ruling in pathology [13]. Due to the lack of established clinical guidance around POCUS in pediatrics, a group of European and North American pediatric intensivists and cardiologists convened to compose evidence based guidelines for critically ill children, and the 20 expert panelists strongly agreed on over 20 recommendations including that POCUS has utility in detection of pneumonia and pleural effusion, multiple line placements and procedures, as well as monitoring conditions such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [14].

Currently, few pediatric POCUS curricula have been published with data supporting its efficacy. Brant et al. at the University of Colorado pediatrics residency program devised a curriculum for all interns comprised of three half-days with both didactics and hand-on application [15]. Comparing pre- and post-course test results revealed a statistically significant increase in scores, and the participants’ post-course objective structured clinical exam (OSCE) scores demonstrated high proficiency in obtaining and interpreting key POCUS views on the FAST exam. Recently, Sabnani et al developed a longitudinal, multimodal POCUS curriculum for pediatric residents consisting of an online question bank combined with in-person learning sessions [16]. Evidence of comparably structured curricula exists sub-specialty pediatric; however, the data gathered is similarly promising [17-19].

Our goal was to develop a consolidated, easily replicable and efficient POCUS curriculum to increase confidence with and proficiency of POCUS skills, primarily within the pediatric inpatient setting.

Methods

Personnel and Location

This curriculum was devised by two pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) physicians who work primarily at a large, tertiary academic children’s hospital, and who regularly work with pediatric residents. The curriculum was designed as an elective, available to second- and third-year residents who expressed interest in POCUS, and whose planned career paths would benefit from a working knowledge of POCUS (i.e., PEM, critical care, neonatal critical care, hospital medicine, and rural general pediatrics). This elective was first offered to pediatric residents in 2017, with a total of 10 participating residents to date, 7 of which completed all the surveys making up our data set (3 residents did not complete the post-survey). Upon graduation, the residents largely went into careers that could incorporate POCUS (4 pediatric emergency medicine, 1 pediatric hospital medicine, 1 global health, 2 child abuse).

Course Curriculum

In the first week of the elective, residents completed online didactics including a structured series of video modules and associated multiple-choice quiz evaluations through an POCUS education program. Topics included ultrasound basics as well as cardiac and extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (eFAST) exams. There were no formal lectures or didactics during the second elective week to maximize faculty efforts in direct scanning sessions.

The second elective week started with an initial simulator session using an advanced US-capable medical manikin. Residents completed 10 cardiac and 10 eFAST cases on a high-fidelity manikin, guided by a PEM US faculty member. The remainder of the hands-on portion took place during 3-4 hands-on sessions in the Primary Children’s Hospital Emergency Department, under the supervision of the previously mentioned PEM faculty, who had POCUS privileges. Scans were performed on patients with consenting families, who were identified by ED staff as clinically stable and accommodating enough to allow an educational scan, and all scanning sessions lasted two hours in duration. If any pathology was found or suspected, it was saved into the picture archive and communication system (PACS) and documented into the EMR. The provider taking care of the patient was informed so they could process this information into the patients care and make any additional follow up recommendations. Additionally, all educational scans were saved in the machine for 1-2 months. Each scan was also logged on paper and scanned into the residents’ electronic academic file for purposes of the elective. Residents were expected to attend a quality assurance session reviewing scans with faculty during their week. Creating and presenting a five-to-ten-minute presentation on a POCUS interesting case or topic found in the literature was the final component of the course.

Ultrasound Indications

Students were taught lung views to assess for pleural effusion, pneumothorax, and A line vs. B line profile, cardiac views of parasternal long, parasternal short, apical four chamber, and sub-xyphoid to assess for gross cardiac function and pericardial effusion, IVC view to assess volume status, and abdominal views of right upper quadrant, left upper quadrant, and pelvis to assess for free fluid and bladder volume. Students also had the opportunity to practice ultrasound needle guidance using a Blue Phantom task trainer made of SimulexUS tissue. These indications were aligned with national standards for POCUS, adapted for the resident level [13-14].

Course Objective

The course administrators’ goal was to increase confidence and competency of the above POCUS indications.

Survey Data Collection

A 15-item Likert scale survey (Table 1) was utilized to assess confidence in the specific POCUS skills and indications learned during the course. This survey was administered before (pre-), immediately after (post-), and at least 18 months after completion of the course and 6 months after the resident had completed residency training (18 m). To obtain the post-residency timepoint, residents were contacted by last phone or email on record with brief explanation of the study and asked for permission to send the survey.

To obtain qualitative data, residents also completed an exit survey immediately following the elective exploring resident thoughts about the structure, content, and suggestive improvements for the course.

Survey Data Analysis

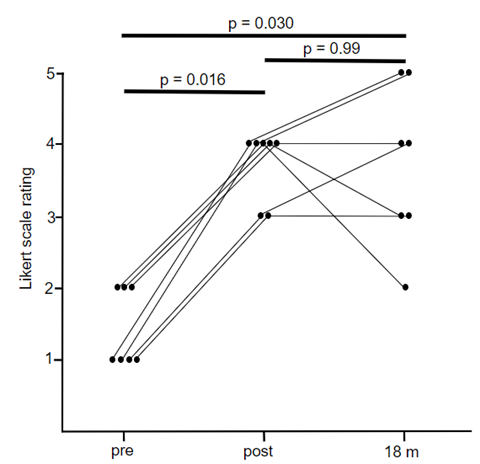

Given the non-parametric nature of our data with a Likert scale survey, data was analyzed using medians both at the individual question and globally by using the median score of all fifteen Likert scale questions per participant. Significance was analyzed using the Wilcoxon paired match test, applied between pre- and post- data, pre- and 18-m data, and post- and 18-m data. A p value of <0.05 was used as a cut off for significant difference.

Qualitative Analysis

Survey data was grouped into topics and analyzed using a thematic coding system in which post-course survey responses were coded based on frequency and emphasis that respondents placed on answers to survey questions [20]. Topics emerged from the analysis of the qualitative data. Following the final round of coding, the codes were classified into overarching themes in preparation for interpreting the data.

IRB Approval

This study was approved by the University of Utah under IRB study 00157801.

Results

Resident confidence across all POCUS domains assayed in the Likert survey increased after the course with pre-survey question median = 2.0 and interquartile range = 1.0 compared to post-survey median 4.0 and interquartile range = 0.5, (n = 7, p = 0.016, response rate 100%). In addition, this increase persisted for at least eighteen months after elective completion with 18-month survey median = 3.0 and interquartile range = 1.5 (n = 7, p = 0.031 compared to pre-survey and p = 0.99 compared with post-survey, response rate 100%) (Figure 1).

In addition, 14 of the 15 questions were also found to be significantly improved after the elective with persistent increase in 13 questions eighteen months after elective completion. The only question which was not found to have a significant increase after the elective was “I am confident finding and obtaining vascular access with POCUS”. Notably residents did have time with a vein simulator but did not have the opportunity to place any peripheral or central access during the elective. This question was also found to be non-significant at the six-month survey time point, in addition to the question “I am confident in my ability to diagnose shock with POCUS” (Table 2).

Our analysis of post-survey responses yielded two major themes. These include: (1) strengths of the elective and (2) participant derived proposals for curriculum development. Descriptive quotations for these themes are included below.

Strengths of the elective were described in the following ways:

- “I feel way more confident in my abilities at the end of the course then I would have ever thought. Also I feel like I know so much more about when to use ultrasound and how amazing it can be in practice.”

- “I appreciated that all scanning was done with a faculty member, and that I received real- time feedback on how to improve the quality of my images”

Participant derived proposals for curriculum development include the following sample responses:

- “Could be cool to follow the sonographers around to get a few more hours of scanning and see how people who do US all the time may do things differently.”

- “More time scanning, less time to complete video lectures…Maybe two more days for scanning and only 3 days for the video lectures”

Discussion

Our study highlights that a short elective, which could be implemented with minimal resources, can have a lasting impact on pediatric residents’ confidence in performing POCUS. Furthermore, resident confidence in ultrasound skills persists after completion of residency. Our elective has attempted to minimize faculty time through the use of online resources, does not require purchase of handheld ultrasounds for the residents, and can fit seamlessly into the current educational structure of most pediatric residency programs.

This study highlights the importance of designing measurable education data at specific time points with POCUS education and training; at the onset of training, after training and at delayed time points, to measure persistence of confidence in performing POCUS. A hybrid model of online education coupled with simulated training and real patient scanning with a skilled instructor achieves long-term resident retention and maintains a 1:1 student/teacher ratio, which residents qualitatively found beneficial, while minimizing faculty resources. Studies involving POCUS education and knowledge retention are needed to determine the most useful data to collect in terms of measuring retention of POCUS knowledge and skill as well as timing of checking retention of skill to maintain POCUS mastery and competency.

Limitations

Several limitations were present in designing and executing this curriculum and study. This study is limited by small sample size and was conducted at a single institution; therefore, it is not clear if this model is broadly generalizable. With a very small number of POCUS-privileged attending physicians, the course was instructor intensive and dependent on their schedules which restricted the number of residents able to participate. As a result, our data was collected over several years of offering the elective in order to obtain the sample size, and it is possible that the sample is heterogeneous given temporal separation. Currently our institution does not offer dedicated funding directed to a resident-oriented POCUS program. As a result, our assessment methods are also limited to resident surveys rather than more formalized skills-based assessments of resident skill.

Using online self-guided didactic material prior to the elective did limit the amount of faculty non-scanning time needed to implement this elective and reduced teaching commitment to only one week; however, it also limited the customization of the curriculum. With more resources available, we would explore the ideal instructor to student ratio (currently 1:1) as well as assess the efficacy of in-person, live-taught didactics versus online, self-directed modules. Faculty teaching time was roughly 9 hours per elective, spread between 3 different faculty equaling approximately 3 hours per resident. While not a major time commitment, this is still a significant demand to ask of faculty when it is unfunded time.

Next Steps

We are currently exploring several next steps. As our study only explores resident confidence, next steps including changing from the confidence survey to a competency-based quiz in alignment with the Kirkpatrick model of evaluation. Increasing the amount of PEM US faculty would further dilute the teaching requirement and may also allow expansion of the elective to more residents, although faculty funding remains a significant barrier. In terms of scheduling, our residency has recently adopted an “X+Y” format with built-in elective weeks every fourth week. Future work will explore partnering with other US departments (PICU, PHM, NICU) to try and develop a longitudinal curriculum which could occur in resident elective weeks. Incorporating other departments could even allow for specialization of the longitudinal experience based on the resident’s intended career path.

Conclusion

This novel two-weeklong intensive elective offered to second and third year pediatric residents increased resident confidence in both obtaining and interpreting ultrasound images in several cardiac and eFAST indications. While other electives have been implemented in pediatrics, this is the first which is only two weeks in duration. In addition, this is the only study we have found which shows persistence in ultrasound confidence for at least eighteen months after elective completion and at least six months after the completion of residency. Thus, despite its short duration, this course appears to be effective in its POCUS content delivery, and could serve as a guide for other pediatric programs to implement ultrasound into their residency curricula.

References

- McGahan JP, Pozniak MA, Cronan J, et al.: Handheld ultrasound: Threat or opportunity?. Applied Radiology. 2015, 20-25. doi: 10.37549/AR2166

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:e27-e54. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.457

- Galen B, Conigliaro R. The Montefiore 10: a pilot curriculum in point-of-care ultrasound for internal medicine residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10:110-111. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00683.1

- Beal E, Sigmond B, Safe-Silski L, Lahey S, Nguyen V, Bahner D. Point-of-care ultrasound in general surgery residency training. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:2577–2584. doi: 10.1002/jum.14298

- Lee L, DeCara JM. Point-of-Care Ultrasound. Review Paper. Current Cardiology Reports. 2020;22(11):1-10. doi:10.1007/s11886-020-01394-y

- Good R, O’Hara K, Ziniel S, Orsborn J, Cheetham A, Rosenberg A. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Training in Pediatric Residency: A National Needs Assessment. Hospital pediatrics. 2021;11(11): 1246-1252. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2021-006060

- Gutierrez P, Berkowitz T, Shah L. et al. Taking the Pulse of POCUS: THe State of Point-of-Care Ultrasound at a Pediatric Tertiary Care Hospital. POCUS Journal 2021; 6(2):80-87. doi: 10.24908/pocus.v6i2.14781

- Liang T, Roseman E, Gao M, Sinert R. The Utility of the Focused Assessment With Sonography in Trauma Examination in Pediatric Blunt Abdominal Trauma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2021;37(2):108-118. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001755

- Alzahrani SA, Al-Salamah MA, Al-Madani WH, Elbarbary MA. Systematic review and meta-analysis for the use of ultrasound versus radiology in diagnosing of pneumonia. Critical ultrasound journal. 2017 Dec 2017;9(1):6. doi:10.1186/s13089-017-0059-y

- Shah V, Tunik M, Tsung J. Prospective evaluation of point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children and young adults. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(2):119-125. doi:10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.107

- Alrajab S, Youssef AM, Akkus NI, Caldito C. Pleural ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of pneumothorax: review of the literature and meta-analysis. Critical care 2013;17(5): R208. doi:10.1186/cc13016

- Hopkins A, Doniger S. Point-of-Care Ultrasound for the Pediatric Hospitalist’s Practice. Hospital pediatrics. 2019;9(9):708-718. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2018-0118

- Le Coz J, Orlandini S, Titomanlio L, Rinaldi V. Point of care ultrasonography in the pediatric emergency department. Italian journal of pediatrics. 2018;44(1):87. doi:10.1186/s13052-018-0520-y

- Singh Y, Tissot C, Fraga M, et al. International evidence-based guidelines on Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) for critically ill neonates and children issued by the POCUS Working Group of the European Society of Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC). Critical care. 2020;24(1):65. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-2787-9

- Brant J, Orsborn J, Good R, Greenwald E, Mickley M, Toney A. Evaluating a longitudinal point-of-care-ultrasound (POCUS) curriculum for pediatric residents. BMC medical education. 2021;21(64). doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02488-z

- Sabnani R, Willard CS, Vega C, Binder ZW. A longitudinal evaluation of a multimodal POCUS curriculum in pediatric residents. POCUS Journal 2023;8(1):65-70. doi:10.24908/pocus.v8i1.16209

- Good R, Orsborn J, Stidham T. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Education for Pediatric Residents in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. MedEdPORTAL : the journal of teaching and learning resources. 2018;14: 10683. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10683

- Bhargava V, Haileselassie B, Rosenblatt S, Baker M, Kuo K, Su E. A point-of-care ultrasound education curriculum for pediatric critical care medicine. The ultrasound journal. 2022;14(44). doi:10.1186/s13089-022-00290-6

- Harel-Sterling M, McLean L. Development of a blended learning curriculum to improve POCUS education in a pediatric emergency medicine training program. CJEM. 2022;24(3):325-328. doi:10.1007/s43678-022-00264-6

- Knox S, Schlosser L. Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. Claire E Hill (ed): 2012.

Figures & Tables

For each of the following statements, please mark the number that best corresponds to your response:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I am confident adjusting the basic knobs such as gain and depth | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident at choosing the correct probe for a given patient and purpose | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident finding and obtaining vascular access with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident at performing either a FAST exam and/or an EFAST exam | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident that I can diagnose pericardial effusion with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident that I can diagnose tamponade with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident that I can diagnose a pneumothorax with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident that I can diagnose fluid in the peritoneum such as hemoperitoneum or ascites with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident in my ability to obtain basic cardiac views with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident in my ability to assess left ventricular function with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident in my ability to perform a thoracic examination with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident in my ability to evaluate right ventricle function and volume overload with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident in my ability to evaluate volume responsiveness with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident in my ability to diagnose shock with POCUS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am confident in my ability to acquire images, interpret them, and clinical integration using POCUS: “putting it all together” | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Questions | Pre- | Post- | 18 m | pre/post p-value | post/18m p-value | pre/18m p-value |

| Q1. I am confident adjusting the basic knobs such as gain and depth | 1 | 5 | 4 | 0.016 | 0.250 | 0.016 |

| Q2. I am confident at choosing the correct probe for a given patient and purpose | 1 | 5 | 4 | 0.016 | 0.500 | 0.016 |

| Q3. I am confident finding and obtaining vascular access with POCUS | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0.063 | 1.000 | 0.125 |

| Q4. I am confident at performing either a FAST exam and/or an EFAST exam | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0.016 | 0.313 | 0.016 |

| Q5. I am confident that I can diagnose pericardial effusion with POCUS | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0.016 | 1.000 | 0.031 |

| Q6. I am confident that I can diagnose tamponade with POCUS | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0.016 | 1.000 | 0.031 |

| Q7. I am confident that I can diagnose a pneumothorax with POCUS | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0.016 | 0.375 | 0.031 |

| Q8. I am confident that I can diagnose fluid in the peritoneum such as hemoperitoneum or ascites with POCUS | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0.016 | 1.000 | 0.016 |

| Q9. I am confident in my ability to obtain basic cardiac views with POCUS | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0.016 | 0.813 | 0.031 |

| Q10. I am confident in my ability to assess left ventricular function with POCUS | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0.016 | 1.000 | 0.016 |

| Q11. I am confident in my ability to perform a thoracic examination with POCUS | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0.016 | 0.750 | 0.031 |

| Q12. I am confident in my ability to evaluate right ventricle function and volume overload with POCUS | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.016 | 0.531 | 0.031 |

| Q13. I am confident in my ability to evaluate volume responsiveness with POCUS | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0.016 | 0.781 | 0.016 |

| Q14. I am confident in my ability to diagnose shock with POCUS | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0.016 | 0.531 | 0.063 |

| Q15. I am confident in my ability to acquire images, interpret them, and clinical integration using POCUS: “putting it all together” | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0.016 | 0.250 | 0.031 |

Medians of the responses of the participants to each question are reported at the time points of prior to the course (pre-), immediately after the course (post-), and at least 18 months after completion of the elective (18 m) along with p-values calculated using the Wilcoxon paired values test (n = 7 for all data points).

Return to Table of Contents: 2023 Journal of the Academy of Health Sciences: A Pre-Print Repository

Increased Pediatric Resident Confidence in Point-of-Care Ultrasound after an Ultrasound Elective by Benjamin Drum, MD, PhD, Bair Diamond, MD, Rachel Hess, MA, Matthew Szadkowski, MD & Matthew Steimle, DO