Table of Contents

Introduction

Simulation-based education (SBE) is used to teach healthcare providers clinical knowledge, communication skills, crisis resource management, and team dynamics [1–4]. However, SBE may be stressful to participants as it exposes educational gaps and often requires performance in front of peers [5,6]. Stress can enhance learning when perceived as positive and challenging or impair learning when perceived as negative and threatening [7–10]. While stress may be inherent in SBE, it remains largely unknown how participants experience stress, which participants are at higher risk of negative stress, and what the best practice is for SBE facilitators to manage participants’ stress. A better understanding of SBE-related stress is needed to identify participants at risk for negative stress and to guide SBE facilitators to prioritize emotional recovery or learning during simulation sessions.

One approach to understanding the impact of stress is examining participants’ self-appraisal of stress known as cognitive appraisal. Individuals appraise a situation in two ways: 1) as a challenge if conscious and subconscious resources outweigh the demands of a task at hand, or 2) as a threat if the demands are greater than available resources [11–15]. Challenge appraisal is associated with benefits likely to impact SBE participants’ learning in a positive way such as increased positive affect and effective adaptive physiologic responses [16,17]. Threat appraisal is likely to negatively impact SBE participants’ learning experience and is incongruent with the principles of psychological safety in simulation environments [18–22].

In this prospective cohort study, we will assess challenge and threat cognitive appraisal among SBE participants before and after a simulation scenario. We will evaluate SBE participant factors associated with their cognitive appraisal including demographics, prior SBE experience, global perceived stress, and baseline risk for anxiety disorders. We hypothesize that most SBE participants will appraise their stress as a challenge rather than a threat, where participants earlier in their career or training and those with less simulation experience being more likely to appraise their stress as a threat. We will also examine whether SBE facilitators are able to identify participants who experience SBE as a threat by using a psychological distress identification tool [5]. We hypothesize that participants assigned higher psychological distress scores will be more likely to appraise their stress as a threat.

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Utah institutional review board. Simulation participants at the Primary Children’s Hospital Simulation Center going through their regularly-scheduled simulation training sessions between March to September 2020 were recruited to take surveys before and after one of their simulation events as part of this study. Most sessions were multidisciplinary and included practicing nurses, patient care technicians, respiratory therapists, and providers such as an attending physician, fellow, resident, nurse practitioner (NP), or physician’s assistant (PA). Some sessions had only nurses, and there were no student participants in this study. The sessions were formative and confidential. All two-hour simulation sessions consisted of a prebrief, a short brief before two simulation scenarios with high-fidelity mannikins each followed by a debrief, and a summary at the end. The sessions were facilitated by Intermountain Health-certified simulation facilitators with a simulation specialist present to operate the mannikin. An unrestricted variety of simulation scenarios were used with variable learning objectives, all chosen from a scenario library by the facilitator to suit the needs of the participant group which ranged from novice to expert. All participants were shown a consent cover letter indicating participation in the study was voluntary prior to accessing the study surveys. Survey responses were collected via REDCap, an internet-based database and survey tool [23]. Surveys were accessed by a QR code linking to REDCap where participants entered a simulation session event number to identify simulation type, and an individual study number assigned to them when they entered the simulation center to keep participant responses anonymous.

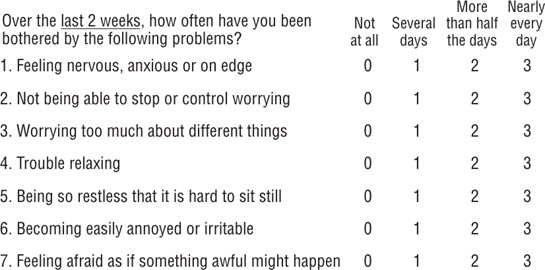

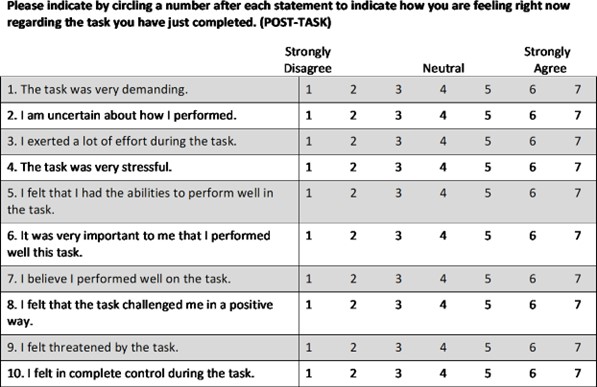

Participants were surveyed at two time points: 1) after the session prebrief and before the first scenario brief, and 2) after the first scenario was complete and before the first debrief. The pre-scenario survey included questions about demographics, healthcare role, prior simulation experience, and the following three surveys: the National Institute of Health (NIH) Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder screening tool (GAD-7), and the Acute Stress Appraisal survey (ASA). See appendix A to view these study surveys.

- NIH PSS: This survey quantifies the degree of perceived stress over the past month by assessing how much control respondents feel they have over their lives. For this 10-item survey, an uncorrected T-score of ≤40 indicates low levels of stress while a score ≥60 suggests high levels of perceived stress [24,25].

- GAD-7: This survey quantifies baseline anxiety through a 7-item survey assessing anxiety symptoms over 2 weeks to measure severity of symptoms and risk of having an anxiety disorder. A total score of 0-4 indicates no anxiety disorder, 5-9 indicates a mild anxiety disorder, 10-14 a moderate anxiety disorder, and more than 14 indicates a severe anxiety disorder [26,27].

- ASA: The Acute Stress Appraisal survey (ASA) determined the cognitive appraisal ratio of threat or challenge and was used with permission from the developer, Wendy Mendes, PhD of University of California San Francisco [28]. This survey is commonly used in psychology research and asks respondents about their capability to handle a stressful task. The survey has two parts with 12 questions answered before a task is completed (ASA pre) and 10 questions answered after the task is done (ASA post) to assess the demands on the participant and resources available to the participant before and after task completion. A threat ratio is then calculated by dividing the demand score by the resource score. A threat ratio >1 indicates the stress associated with a task is threatening (demands exceed resources) while a ratio ≤1 indicates the stress associated with a task is challenging (resources exceed demands). Each participant filled out the ASA pre that was part of the first survey before the brief of the first simulation scenario, and filled out the ASA post in the second survey after the scenario was complete and before the debrief was done.

Session facilitators were all clinical personnel who regularly facilitate simulation sessions, but none were psychologists or psychiatrists. At the end of the simulation session, the session facilitator assigned each participant a psychological distress level (PDL). This level was determined by using the Simulation Psychological Distress Algorithm, a measure designed by Henricksen, et al. to assist facilitators in recognizing and beginning to assist any simulation participant who may be in a psychologically distressed state [5]. The algorithm has four levels of distress: 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), and 3 (severe). Levels are based on facilitator-observed behavior that may indicate psychological distress such as participant withdrawal from the group, tearfulness, anger or raised voice. The PDL was matched to participant surveys in REDCap by the assigned individual study number. Every facilitator scored simulation participants on the PDL scale at the time of the simulation session and were blinded to all participant survey results such as baseline anxiety levels and stress appraisal. Each facilitator had immediate access to select study authors (Coker and Dahmen) to collaborate regarding PDL scoring of each participant to minimize inter-rater scoring differences. Each session only had one facilitator.

Statistical Analysis. Participants were excluded from analysis if they did not complete both the pre and post scenario surveys. Demographics and clinical outcomes of interest were summarized using mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. For categorical variables, counts and percentages were reported. Participants were categorized into one of four outcome groups based on the stress state from the ASA pre and post surveys: Challenge/Challenge, Challenge/Threat, Threat/Challenge, and Threat/Threat. Demographic, PSS, and GAD-7 data were compared between these four groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for skewed continuous variables and chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Univariable logistic regression models evaluated the association between the dichotomized outcome Challenge/Challenge versus the other three combinations (Challenge/Threat, Threat/Challenge, and Threat/Threat) for each variable of interest. Variables with p-value<0.10 were included in a multivariable logistic model. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Statistical significance was assessed at the 0.05 level. PDL and ASA scores were compared in a cross-tabulation table using Fisher’s exact tests. Statistical analyses were implemented using R v. 4.0.3 (R Core Team, 2020).

Results

Five-hundred and fifty-one pediatric healthcare personnel participated in the study. Four hundred eighty-five (485) participants completed both surveys and sixty-six (66) participants completed only one of the surveys and were therefore excluded due to incomplete data. A summary of demographic information, job variables, simulation experience and type, and PSS, GAD-7, and ASA pre/postsurvey scores are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were nurses (n=347, 71.5%). Forty-three (43) medical trainees participated in the study, and 40% were in their first year of training. The majority (92.2%) of participants had completed at least one simulation session in the past two years. Almost half (48.7%) of simulation scenarios were for non-critical care groups working in the medical/surgical unit, same day surgery center, or post-anesthesia care unit. The vast majority (99.4%) of participants scored 40 or less on the PSS, indicating low perceived stress over the last month (median 32, IQR 30-34). On the GAD-7, 80.3% of participants scored in the “no” or “mild” anxiety disorder range.

The four ASA state groups are compared in Table 2. The majority of participants (n=325, 67.6%) appraised their stress as a challenge before and after the simulation scenario (Challenge/Challenge). Eighty-one participants (16.7%) appraised their stress as a threat before the scenario and a challenge after the scenario (Threat/Challenge). 9.9% and 5.8% were in the Challenge/Threat and Threat/Threat groups, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference between the four ASA state groups when looking at job type, simulation type, years in practice and training, and anxiety disorder scores. There was no statistically significant difference in prior SBE participation, gender, and chronic stress scores between the four groups. Results of logistic regression analysis comparing the Challenge/Challenge group to the other three ASA state groups are shown in Table 3. Univariable logistic regression showed that nurses and assistive personnel (patient care technicians and respiratory therapists) were more likely to appraise their stress as a challenge rather than a threat compared to advanced providers (attending physicians, NPs, and PA’s). Trainees (residents and fellows) were analyzed separately from attending physicians. When compared to advanced providers, assistive personnel were 10 times more likely to be in the Challenge/Challenge group (p<0.001, OR 10.31172[3.15-38.05]), and nurses were 4 times more likely to be in the Challenge/Challenge group (p=0.012, OR 4.09[1.42-13.38]). Simulation type and chronic stress scores were not significant in univariable regression analysis. Prior simulation experience was variably significant, with those who attended three or more simulation sessions in the past two years ultimately being more likely to appraise stress as a challenge in multivariate analysis. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, nurses, assistive personnel, and participants with lower anxiety disorder scores continued to be significantly more likely to appraise stress as a challenge.

Table 4 displays results comparing participant ASA scores with facilitator-assigned PDL scores. Of 23 participants in the Threat/Threat group, one was given a distress score 1 or higher. Thirteen participants were given a distress score 1 or higher out of 282 participants in the Challenge/Challenge group. Overall, there was no association between the PDL and ASA scoring (p>0.99).

Discussion

Our survey study of cognitive appraisal in SBE participants primarily aimed to categorize simulation-induced stress as challenging or threatening and to identify participant and simulation factors predictive of cognitive appraisal. This is the largest and only multidisciplinary study of cognitive appraisal in SBE.

Other studies have used the challenge and threat stress state to characterize simulation participants. Carenzo, et al. showed that residents in a simulation-based competition performed better when they were in a challenge state with a high level of resources until demands increased, shifting towards a threat state [29]. In their study, a greater level of training and higher self-confidence were associated with challenging stress, and state anxiety levels were not. Harvey, et al. showed that threat appraisal is associated with more difficult simulation scenarios and higher salivary cortisol levels [30]. In contrast to these studies, our study did not show that simulation type was significantly associated with the challenge or threat state, perhaps indicating there were participants who appraised their stress as a challenge and threat in every type of simulation despite any level of simulation difficulty. Also, our study used the GAD-7 which measures risk for an anxiety disorder rather than state anxiety levels and we made no attempt to correlate participant physiology to psychology.

This study defined four groups of simulation participants depending on their stress appraisal before and after simulation: Challenge/Challenge, Challenge/Threat, Threat/Challenge, and Threat/Threat. We found that 68% of participants appraised their stress surrounding a simulation scenario as a challenge rather than a threat before and after simulation (Challenge/Challenge group). Nurses and assistive personnel had higher odds of appraising simulation stress as a challenge compared to advanced providers. Lower anxiety disorder screening scores and more simulation experience were also associated with the Challenge/Challenge appraisals.

Advanced providers were less likely to be in the Challenge/Challenge group than nurses and assistive staff. This may be because advanced providers are often expected to take the team leader roles and may have more expectations placed on them during a scenario either by themselves or by other participants. They may worry about a loss of respect from the rest of the multidisciplinary team when knowledge gaps are revealed. Trainees were not significantly different from advanced providers on univariable analysis.

Our findings support our hypothesis that most SBE participants appraise simulation-induced stress as a challenge. Challenge appraisal indicates participants feel they have the experience, knowledge, and skills (i.e., resources) to confront the simulation scenario even if the content is unfamiliar to them. Challenging stress is associated with improved performance and personal growth [13,29].

It seems intuitive that some (17% in our study) who appraise their stress as a threat before simulation were relieved when the simulation was done and appraised their stress as a challenge after simulation (Threat/Challenge group). We recognize that less than 6% of participants appraised their stress as a threat before and after simulation (Threat/Threat group), and some (~10%) appraised their stress a challenge before simulation and switched to threat after simulation (Challenge/Threat group). These last two groups are intriguing and warrant more study.

We further aimed to evaluate facilitators’ abilities to accurately identify participants whose ASA scores would indicate they are in a threatened stress state by having the facilitators assign PDL scores. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was no relationship between PDL and ASA scores. This indicates facilitators are not able to accurately associate observed simulation participant behaviors with a participant’s appraisal of stress. Henricksen, et al previously showed that PDL scores > 0 are rare in simulation, occurring in <1% of participants [5]. In our study, 4% of participants had a PDL of 1 or higher. Yet, despite a higher incidence of PDL scores, there was no correlation to ASA scoring. Unless a participant is having an exceptional emotional response, it may be near impossible to know who is in a threatened state.

Healthcare providers are trained to work in stressful conditions and can internally regulate their emotions while remaining functional in their jobs [31]. What is perceived as distress by a facilitator may be excitement or distraction for a participant. All personnel have impression management skills that can defy facilitators’ skills in detecting most threatening stress [32,33]. Thus arises a debriefing conundrum where most SBE participants are in a challenge state and ready to learn, but a small percentage of participants exist in a hidden threatened state.

We propose that pragmatic debriefing with emotional surveillance be used to help the majority of simulation participants obtain maximal simulation benefit. Most particpants are likely to be in a challenge state and all participants have impression management skills that may defy facilitator identification of psychological distress. Thus, those in a threatened state are hidden amongst simulation participants. By focusing on learning objectives as well as discovering what happened and what consequences of actions occurred during simulation, debriefing can concentrate on improving performance. Being watchful for signs of psychological distress will help every facilitator maintain awareness that simulation is threatening to some participants, and there may be a participant that needs special attention. Monitoring participants for psychological distress and offering assistance when appropriate is what we can do to help those in a threatened state, given the difficulty of identifying them. Incidentally, helping each team member improve may help them psychologically rather than exposing their threatened state to every participant.

This study does have limitations. Generalizability of these results may be limited since this is a single center study. Employees providing direct patient care at Primary Children’s Hospital are required to attend simulation sessions with their units at least once a year and are frequently exposed to the concept of psychological safety. Our institutional culture may make SBE participants more comfortable in the simulation center than in an institution where simulation is less routine, and may have affected study results. Institutional simulation culture may need to be understood better to understand stress in simulation. Our study population may also affect generalizability. Nurses were well represented, but other types of healthcare providers such as resident and fellow trainees were a smaller proportion of the study population making it difficult to draw absolute conclusions about this group. Although study authors were available to assist facilitators in assigning PDL scores to each study participant, inter-rater reliability was not measured because of study authors’ availability to every facilitator. Thus, assigned PDL scores were given from the perspective of two consistent study personnel and a session facilitator who all observed the study participants and the scores may be subject to any observer bias they may have had. Further research with a more balanced study population would make it easier to assess differences between advanced practitioners, nurses, trainees, and assistive personnel. Also, we did not study the effect of debriefing on cognitive stress appraisal. We assessed stress states immediately after a simulation scenario but before debriefing. It is possible that debriefing can provide support to SBE participants and change their cognitive appraisal to favor a challenge state. Future studies could repeat the ASA post survey after debriefing to investigate if debriefing changes a participant’s cognitive appraisal. Different debriefing strategies could be studied using this ASA survey as well. Finally, data collection was interrupted by quarantine procedures during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited study participation and had an unknown effect on the baseline stress and anxiety of the participants.

This was a prospective cohort study assessing cognitive stress appraisal in participants engaged in multidisciplinary simulation scenarios. The results show that SBE stress is mostly appraised as a challenge, particularly for nurses, respiratory therapists, and patient care technicians compared to attending physicians, NPs, and PAs. More prior simulation experience and lower anxiety disorder risk scores were also associated with greater likelihood of challenge appraisal whereas time in healthcare role, chronic stress, and simulation type were not significant on multivariable analysis. Self-reported participant threatened stress appraisal was not correlated to facilitator-assigned distress scores, indicating facilitators are not likely to detect threatened participants by their behavior. The debate on whether to concentrate on the learning and improvement of the challenged majority or the emotional evaluation of the hidden and threatened minority may begin.

References

- Cheng A, Lang T, Starr S, Pusic M: Technology-enhanced simulation and pediatric education: a meta-analysis. Am Acad Pediatrics 2014; Accessed September 5, 2019. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/5/e1313.abstract

- Dunn W, Dong Y, Zendejas B, Ruparel R, Farley D: Simulation, mastery learning and healthcare. The American journal of the medical sciences 2017; 353(2):158-165.

- Lopreiato JO, Sawyer T: Simulation-based medical education in pediatrics. Academic Pediatrics 2015; 15(2):134-142.

- Mileder LP, Schmölzer GM: Simulation-based training: The missing link to lastingly improved patient safety and health? Postgraduate Medical Journal 2016; 92(1088):309-11.

- Henricksen JW, Altenburg C, Reeder RW: Operationalizing healthcare simulation psychological safety. Simulation in Healthcare 2017; 12(5):289-97.

- Gouin A, Damm C, Wood G, et al: Evolution of stress in anaesthesia registrars with repeated simulated courses: An observational study. Anaesthesia, critical care & pain medicine 2017; 36(1):21-6.

- Joels M, Pu Z, Wiegert O, Oitzl MS, Krugers HJ: Learning under stress: how does it work? Trends in cognitive sciences 2006; 10(4):152-8.

- de Kloet ER, Oitzl MS, Joëls M: Stress and cognition: are corticosteroids good or bad guys? Trends in Neurosciences 1999; 22(10):422-6.

- Schwabe L, Wolf OT: Learning under stress impairs memory formation. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 2010 ;93(2):183-8.

- Yerkes RM, Dodson JD: The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology 1908; 18(5):459-82.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S: Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, Springer publishing company, 1984.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S: Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality 1987; 1(3):141-69.

- vonRosenberg J: Cognitive appraisal and stress performance: The Threat/Challenge matrix and its implications on performance. Air Medical Journal 2019; 38(5):331-333.doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2019.05.010

- Hulbert-Williams NJ, Morrison V, Wilkinson C, Neal RD: Investigating the cognitive precursors of emotional response to cancer stress: Re-testing Lazarus’s transactional model. British Journal of Health Psychology 2013; 18(1):97-121. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02082.x

- Gaab J, Rohleder N, Nater UM, Ehlert U: Psychological determinants of the cortisol stress response: the role of anticipatory cognitive appraisal. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005;30(6):599-610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.001

- Tomaka J, Blascovich J, Kibler J, Ernst JM: Cognitive and physiological antecedents of threat and challenge appraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1997;73(1):63-72. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.63

- Blascovich J, Tomaka J: The biopsychosocial model of arousal regulation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1996; Vol. 28. Academic Press; 1996:1-51.doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60235-X

- Gardner R: The role of debriefing in simulation-based education. Seminars in perinatology 2013; 37(3):166-174. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2013.02.008

- Gardner R: Introduction to debriefing. Seminars in perinatology 2013; 37(3):166-174.doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2013.02.008

- Rudolph JW, Raemer DB, Simon R: Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: the role of the presimulation briefing. Simulation in Healthcare 2014;9(6):339-349. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000047

- Rudolph JW, Simon R, Dufresne RL, Raemer DB: There’s no such thing as “nonjudgmental” debriefing: a theory and method for debriefing with good judgment. Simulation in Healthcare 2006; 1(1):49-55. doi:10.1097/01266021-200600110-00006

- Brett-Fleegler M, Rudolph J, Eppich W, et al: Debriefing assessment for simulation in healthcare: development and psychometric properties. Simulation in Healthcare 2012;7(5):288-294. doi:10.1097/SIH.0b013e3182620228

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG: Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- NIH Toolbox® Scoring and Interpretation Guide for the IPad NIH Toolbox ® Scoring and Interpretation Guide for the IPad.; 2006.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R: A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1983; 24(4):385-396.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B: A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. https://jamanetwork.com/

- Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al: Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care 2008;46(3):266-274. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40221654

- Mendes W (UCSF). Acute stress appraisals. 2017;(March):1-3.

- Carenzo L, Braithwaite EC, Carfagna F, et al: Cognitive appraisals and team performance under stress: A simulation study. Medical Education 2020; 54(3):254-263.doi:10.1111/medu.14050

- Harvey A, Nathens AB, Bandiera G, Leblanc VR: Threat and challenge: Cognitive appraisal and stress responses in simulated trauma resuscitations. Medical Education 2010; 44(6):587-594. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03634.x

- Thompson NJ, Corbett SS, Welfare M: A qualitative study of how doctors use impression management when they talk about stress in the UK. International Journal of Medical Education 2013; 4:236-246. doi:10.5116/ijme.5274.f445

- Murphy NA: Appearing Smart: The impression management of intelligence, person perception accuracy, and behavior in social interaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2007; 33(3):325-339. doi:10.1177/0146167206294871

- Bell E, McAllister S, Ward PR, Russell A: Interprofessional learning, impression management, and spontaneity in the acute healthcare setting. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2016; 30(5):553-558. doi:10.1080/13561820.2016.119

Tables

Table 1. Summary of demographics and survey scores

| Current Job Position/Credentials | Chronic stress/PSS scores | ||

| Advanced providers: Attending + NP + PA | 15 (3.1%) | ≤40 low stress | 482 (99.4%) |

| Assistive personnel: Tech + Resp Therapist + other | 80 (16.5%) | 40-60 moderate stress | 3 (0.6%) |

| Nurse | 347 (71.5%) | Mean (SD) | 31.9 (3.3) |

| Trainees: Resident + Student + Fellow | 43 (8.9%) | Median (IQR) | 32.0 (30, 34) |

| Current Year in Training (PGY) 1 | 17 (39.5%) | Range | (10, 43) |

| 2 | 10 (23.3%) | Chronic anxiety/GAD-7 scores | |

| 0-4 minimal anxiety | 203 (41.9%) | ||

| 3 | 6 (14%) | 5-9 mild anxiety | 186 (38.4%) |

| 4 | 5 (11.6%) | 10-14 moderate anxiety | 74 (15.3%) |

| 5+ | 5 (11.6%) | 15+ severe anxiety | 22 (4.5%) |

| Years in Practice | Mean (SD) | 5.9 (4.4) | |

| <2 | 123 (27.8%) | ||

| 2-5 | 95 (21.5%) | Median (IQR) | 5.0 (2, 8) |

| 5-10 | 93 (21%) | Range | (0, 21) |

| 10+ | 131 (29.6%) | ASA pre scores <1 stress is a challenge | 376 (77.5%) |

| Mean (SD) | 7.6 (8.3) | >1 stress is threat | 109 (22.5%) |

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (1.5, 10) | Mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.4) |

| Range | (0, 40) | Median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.6, 1) |

| SBE participation (# sessions in past 2 years) | Range | (0.1, 2.6) | |

| 0 | 38 (7.8%) | ||

| 1 | 65 (13.4%) | ASA post scores <1 stress is a challenge | 409 (84.3%) |

| 2 | 192 (39.6%) | >1 stress is threat | 76 (15.7%) |

| 3 | 81 (16.7%) | Mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.3) |

| 4 | 40 (8.2%) | Median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) |

| 5+ | 69 (14.2%) | Range | (0.1, 2.6) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 427 (88%) | ||

| Male | 58 (12%) | ||

| Simulation type | |||

| Dental Clinic | 13 (2.7%) | ||

| ED/Obs unit | 68 (14%) | ||

| PICU Fellows Boot Camp | 15 (3.1%) | ||

| Med/Surg + Outpatient Procedures/PACU | 236 (48.7%) | ||

| ECMO | 16 (3.3%) | ||

| NICU | 14 (2.9%) | ||

| Nurse Residency | 56 (11.5%) | ||

| PICU | 67 (13.8%) |

Table 2. Summary of baseline variables stratified by ASA scores before and after a simulation scenario

| All: N=485 | Challenge/Challen ge (C/C): N=328 | Challenge/Thre at (C/T): N=48 | Threat/Challen ge (T/C): N=81 | Threat/Thre at (T/T): | p-value | |

| Current Job Position/ | N=28 | <0.001s | ||||

| Credentials | ||||||

| Attending Physician + NP + PA | 15 (3%) | 5 (1.5%) | 6 (12.5%) | 3 (3.7%) | 1 (3.6%) | |

| Tech + Resp Therapist + | 80 (16%) | 67 (20.4%) | 3 (6.2%) | 6 (7.4%) | 4 (14.3%) | |

| Other Nurse | 347 | 233 (71%) | 33 (68.8%) | 66 (81.5%) | 15 (53.6%) | |

| (72%) | ||||||

| Resident + Student + Fellow | 43 (9%) | 23 (7%) | 6 (12.5%) | 6 (7.4%) | 8 (28.6%) | |

| Current Year in Training (PGY) | 0.048f | |||||

| 1 | 17 (40%) | 6 (26.1%) | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (50%) | 7 (87.5%) | |

| 2 | 10 (23%) | 8 (34.8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 3 | 6 (14%) | 4 (17.4%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 4 | 5 (12%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 5+ | 5 (12%) | 3 (13%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Years in Practice | 0.029s | |||||

| <2 | 123 | 76 (24.9%) | 19 (45.2%) | 19 (25.3%) | 9 (45%) | |

| (28%) | ||||||

| 2-5 | 95 (21%) | 67 (22%) | 2 (4.8%) | 21 (28%) | 5 (25%) | |

| 5-10 | 93 (21%) | 70 (23%) | 9 (21.4%) | 13 (17.3%) | 1 (5%) | |

| 10+ | 131 | 92 (30.2%) | 12 (28.6%) | 22 (29.3%) | 5 (25%) | |

| SBE participation (# | (30%) | 0.26s | ||||

| sessions in past 2 years) | ||||||

| 0 | 38 (8%) | 21 (6.4%) | 9 (18.8%) | 5 (6.2%) | 3 (10.7%) | |

| 1 | 65 (13%) | 40 (12.2%) | 6 (12.5%) | 12 (14.8%) | 7 (25%) | |

| 2 | 192 | 135 (41.2%) | 16 (33.3%) | 34 (42%) | 7 (25%) | |

| (40%) | ||||||

| 3 | 81 (17%) | 58 (17.7%) | 4 (8.3%) | 13 (16%) | 6 (21.4%) | |

| 4 | 40 (8%) | 28 (8.5%) | 4 (8.3%) | 6 (7.4%) | 2 (7.1%) | |

| 5+ | 69 (14%) | 46 (14%) | 9 (18.8%) | 11 (13.6%) | 3 (10.7%) | |

| Gender: Female | 427 | 284 (86.6%) | 41 (85.4%) | 77 (95.1%) | 25 (89.3%) | 0.16f |

| Chronic stress/PSS scores | (88%) | 0.30k | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 32 (30, | 32 (30, 33.2) | 32 (29, 34) | 33 (30, 35) | 32 (30, 34) | |

| Chronic anxiety/GAD-7 | 34) | 0.004k | ||||

| scores Median (IQR) Simulation type | 5 (2, 8) | 5 (2, 8) | 5 (2, 8.2) | 6 (4, 8) | 9 (5, 12) | <0.001s |

| Dental Clinic | 13 (3%) | 8 (2.4%) | 1 (2.1%) | 4 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| ED/Obs Unit | 68 (14%) | 52 (15.9%) | 4 (8.3%) | 10 (12.3%) | 2 (7.1%) | |

| PICU Fellows | 15 (3%) | 7 (2.1%) | 4 (8.3%) | 1 (1.2%) | 3 (10.7%) | |

| Med/Surg + Outpatient | 236 | 167 (50.9%) | 12 (25%) | 40 (49.4%) | 17 (60.7%) | |

| Procedures/PACU | (49%) | |||||

| ECMO | 16 (3%) | 6 (1.8%) | 3 (6.2%) | 5 (6.2%) | 2 (7.1%) | |

| NICU | 14 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Nurse Residency | 56 (12%) | 28(8.5%) | 16(33.3%) | 8(9.9%) | 4(14.3%) | |

| PICU | 67 (14%) | 50(15.2%) | 8(16.7%) | 9(11.1%) | 0(0%) |

Summary of participant characteristics and survey scores grouped by combination of cognitive appraisal of challenge or threat before and after a simulation scenario. Results are expressed as mean and percentage unless otherwise indicated.

Table 3. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression comparing Challenge/Challenge to all others

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Current Job Position/Credentials | ||||

| Attending Physician + NP + PA | Reference | |||

| Tech + RT + other | 10.31 | <0.001 | 16.4 (4.58,66.09) | <0.001 |

| (3.15,38.05) | ||||

| Nurse | 4.09 (1.42,13.38) | 0.012 | 4.9 (1.58,17.08) | 0.008 |

| Resident + Student + Fellow | 2.3 (0.69,8.45) | 0.18 | – | – |

| Current Year in Training (PGY) | ||||

| 1 | Reference | |||

| 2 | 7.33 (1.33,60.29) | 0.034 | – | – |

| 3 | 3.67 (0.55,32.7) | 0.20 | – | – |

| 4 | 1.22 (0.13,9.56) | 0.85 | – | – |

| 5+ | 2.75 (0.36,25.76) | 0.33 | – | – |

| Years in Practice | ||||

| < 2 | Reference | |||

| 2-5 | 1.48 (0.84,2.64) | 0.18 | 1.14 (0.6,2.17) | 0.69 |

| 5-10 | 1.88 (1.05,3.45) | 0.037 | 1.5 (0.76,2.97) | 0.24 |

| 10+ | 1.46 (0.87,2.47) | 0.16 | 1.52 (0.83,2.8) | 0.18 |

| SBE participation (# sessions in past 2 years) 0 | Reference | |||

| 1 | 1.3 (0.57,2.92) | 0.53 | 1.65 (0.66,4.23) | 0.29 |

| 2 | 1.92 (0.93,3.9) | 0.07 | 2.2 (0.92,5.33) | 0.08 |

| 3 | 2.04 (0.91,4.57) | 0.08 | 2.68 (1.04,7.02) | 0.042 |

| 4 | 1.89 (0.75,4.88) | 0.18 | 2.96 (1.02,8.9) | 0.049 |

| 5+ | 1.62 (0.72,3.66) | 0.24 | 2.73 (1.05,7.24) | 0.04 |

| Gender – Male | 1.58 (0.86,3.08) | 0.16 | – | – |

| Chronic stress/PSS scores | 0.97 (0.91,1.03) | 0.28 | – | – |

| Chronic anxiety/GAD-7 scores | 0.95 (0.91,0.99) | 0.011 | 0.93 (0.89,0.98) | 0.005 |

| Simulation type | ||||

| Dental Clinic | Reference | |||

| ED/Obs Unit | 2.03 (0.55,7.01) | 0.27 | – | – |

| PICU Fellows | 0.55 (0.11,2.44) | 0.43 | – | – |

| Med/Surg + Outpatient Surg/PACU | 1.51 (0.44,4.7) | 0.48 | – | – |

| ECMO | 0.38 (0.08,1.65) | 0.20 | – | – |

| NICU | 1.56 (0.31,8.28) | 0.59 | – | – |

| Nurse Residency | 0.63 (0.17,2.11) | 0.46 | – | – |

| PICU | 1.84 (0.5,6.31) | 0.34 | – | – |

Table 4: Cross-tabulation of Psychological Distress Level (PDL) versus Acute Stress Appraisal (ASA) scores

| PDL | ASA | |||||||||||||

| C/C + C/T + T/C | T/T | C/T + T/C + T/T | C/C | |||||||||||

| No distress (=0) | 391 | 23 1 | 132 | 282 | ||||||||||

| Distress (=1/2/3) | 18 | 6 | 13 | |||||||||||

| Cross-tabulation of Participant Distress Level (PDL) assigned by simulation facilitator with Acute Stress Appraisal scores indicated by participants. | ||||||||||||||

Appendix

Return to Table of Contents: 2023 Journal of the Academy of Health Sciences: A Pre-Print Repository

Simulation Stress: Positive Challenge or Negative Threat? by Angela Coker, MD, Deirdre Caplin, PhD. MS, Brian F. Flaherty, MD, Stefanie Pease-Romero, MSN, RN, CHSE, Wendy Dahmen, MSN-Ed, RN, Angela P. Presson, PhD, MS, Zhining Ou, MS & Jared W. Henricksen, MD, MS-HPEd