Abstract

Aims: The primary aim was to assess lay midwives’ knowledge about preeclampsia after an educational activity. The secondary and third aims were to assess lay midwife knowledge retention about preeclampsia and about obstetrical emergencies.

Design: A pretest-posttest evaluation was used to assess lay midwife knowledge and knowledge retention about preeclampsia and obstetrical emergencies.

Methods: Through a partnership among three organizations, an evidence-based educational activity was conducted to enhance lay midwives’ knowledge about preeclampsia. Activities included repetition, role plays, storytelling, hands-on practice, and return demonstrations. Preeclampsia Reminder Cards were modified to increase visual literacy. A 17-item pre-posttest was used to evaluate changes in lay midwives’ knowledge. Knowledge retention was assessed about obstetrical emergencies and preeclampsia.

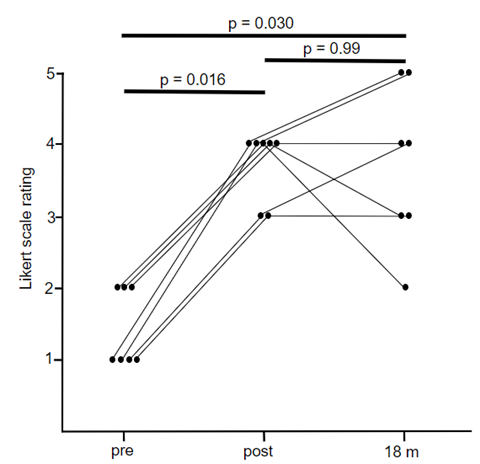

Results: Eleven lay midwives participated in the preeclampsia study. The average pretest score was 32% compared to the average posttest score of 88%. All midwives returned a year later. The average knowledge retention score was 66%. Seventeen lay midwives participated in an obstetrical emergency study with nine returning. The average knowledge retention score was 73% on a six-item survey compared to 51% on the pretest and 85% on the posttest.

Conclusions: Culturally relevant educational activities increase lay midwife knowledge and knowledge retention about preeclampsia and obstetrical emergencies.

Introduction

Guatemala is one of the few Latin American countries in which approximately 50% of the people self-identify as indigenous (United States Agency for International Development [USAID], 2022). Heath inequities persist among indigenous and nonindigenous people, particularly in women of reproductive age (Every Mother Counts, 2022). The maternal mortality rate (MMR) in Guatemala is 95 deaths per 100,000 births which is ranked 75th in the world and second in Central America, after Nicaragua (Central Intelligence Agency, 2020).

Approximately 90% of rural births (Summer, 2019) and 60 to 70% of all births in Guatemala occur at home (Zelter, 2018) in part due to lack of institutional capacity, health care associated with financial (Goldman, 2001) and geographical constraints, and cultural and linguistic marginalization (Every Mother Counts, 2022). The majority of the home births are attended by lay midwives (Juarez, 2020), also known as comadronas in Spanish. Because lay midwives come from the same communities they serve and speak the local language, they are trusted and respected; therefore, play a significant role in women’s health (Goldman, 2001).

While lay midwives are affordable practitioners who play a pivotal role in assisting pregnant women to birth at home in Guatemala (Goldman, 2001); lay midwives often lack knowledge about obstetrical emergencies (Lang, 1997, Roost et al, 2004, Walsh, 2006), such as preeclampsia, which is the second leading cause of maternal death in the country after postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) (USAID, 2017).

The Guatemala Ministry of Health (MOH) had offered trainings since 1955 for lay midwives, however, many issues are evident with the trainings (Goldman & Glei, 2000, Lang, 1997). Lay midwife trainings are offered sporadically, taught in Spanish with written material even though many lay midwives are indigenous, speak Mayan dialects (including Kaqchikel), and have low literacy (Fahey, 2013: Hernandez, 2017, Kestler et al., 2013, Maupin, 2009; Walker, 2015).

Additionally, MOH registered nurses (RNs) with a minimum of a one year of experience, not necessarily in birth, teach the trainings, (Goldsman, 2001) sometimes criticizing lay midwife practices (Goldman & Glei, 200; Greenberg, 1982, Maupin, 2008). The trainings focus on recognizing “the signs of danger” and transferring the pregnant patients to hospitals (Foster et al., 2004; Zelter, 2018) even though many barriers exist for transfer.

Further, no evaluations occur to determine if the trainings change lay midwife knowledge, practice, and ultimately improve maternal and newborn outcomes (Lang, 1997; Foster et al., 2004). Unfortunately, the MOH’s approach to training lay midwives has not improved outcomes (Bailey et al, 2002) and amplifies health inequities for women who birth at home, as evidenced by the Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) in Guatemala not decreasing statistically in more than 20 years (Chary et al., 2012).

Four articles regarding MOH trainings found lay midwives did not use information from the trainings because their knowledge and practices were dismissed during the trainings (Greenburg, 1982; Maupin, 2008; Hinojosa, 2004), or because the information was not provided in their language (Lang, 1997). Two other articles found lay midwife practice is guided more by spirituality than information provided in MOH trainings (Roost, 2004; Walsh, 2006).

All six articles recommended providing information in the native language of speakers, orally for low-literacy audiences with educational activities, such as role plays, hands-on activities, repetition and return demonstrations, and to respect and integrate lay midwife knowledge and practices. These suggestions were implemented in three studies where lay midwife knowledge about PPH and obstetrical emergencies changed significantly after participating in culturally sensitive educational activities (Garcia et al., 2012; Garcia et al., 2018, Garcia, 2022).

The culturally appropriate education was tailored and framed from the perspective of the target population—engaging with local culture is important to determine how culture influences behavior (Thomas et al., 2004). For example, the primary investigator (PI) designed a Preeclampsia Reminder Card (Appendix A) by combining drawings from “Signs of Danger” in the MOH’s Birth Log and the Home-Based Life Saving Skills (HBLSS) curriculum from the American College of Nursing Midwives (ACNM), which has been field tested throughout the developing world (Sibley, et al., 2010).

Lay midwives in past educational activities understood simple color drawings of the “Signs of Danger” from a MOH Birth Log better than complex, black and white drawings from the HBLSS (Garcia, 2022). Thus, reminders of the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia were created from the MOH drawings, and reminders of interventions came from the HBLSS, as the MOH does not offer visual representations of interventions.

Other lay midwife training methods that have demonstrated improved outcomes among pregnant women and neonates include providing adequate consultation for lay midwives (Juarez et al., 2020), lay midwives teaching lay midwives (Hernandez et al., 2017), and intensively training lay midwives (Foster, 2004; Thompson et al., 2014). Components of all of these studies included providing information orally in the native language of participants, and respecting and integrating lay midwife knowledge and practices.

A fifth study found intensive training of lay midwives decreased postpartum complications, but did not improve lay midwives’ detection and hospital referral for obstetrical emergencies (Bailey et al., 2002). This study did not mention if the training was provided orally in the native language of participants and if lay midwife knowledge and practices were respected.

We focused on culturally sensitive educational activities presented orally in the native language as participants, as these methods enjoyed the most evidence in the literature.

Also critical to improving lay midwife knowledge is consistent educational reinforcement (Mosby et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2009). Even though this project focused on presenting new content to the lay midwives, we were also able to assess knowledge retention a year after the educational activity about preeclampsia and three years after a prior educational activity about obstetrical emergencies.

This project, which was a partnership among the MOH, expert faculty in the College of Nursing at the University of Utah (UU), and the non-profit organization Refuge International, took place in San Raymundo, an urban municipality in the highlands of northeast Guatemala.

Aims

The primary aim for the project was to improve low-literacy lay midwives’ knowledge about preeclampsia in San Raymundo using culturally relevant educational activities. A secondary aim was to assess knowledge retention about preeclampsia a year after the original educational activity. A final aim was to assess knowledge retention three years after a previous culturally appropriate educational activity with lay midwives about recognizing obstetrical emergencies.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional pre-posttest evaluation was used to examine the effect of an evidence-based learning activity on lay midwife knowledge about preeclampsia. Participants received laminated Preeclampsia Reminder Cards to reinforce information presented in the educational activity. The project also included a posttest to evaluate lay midwife knowledge retention about preeclampsia a year after the original teaching, and a posttest to evaluate knowledge retention about obstetrical emergencies three years after a learning activity about obstetrical emergencies. A UU Internal Review Board granted the study permission. A checklist for the Strengthening Reporting of Observational Studies (STROBE) was followed in reporting this study. The study met all nine of the ACNM global competencies and skills (ACNM Division of Global Engagement, 2017).

Sample

The target population consisted of 11 lay midwives at a Refuge International health clinic in San Raymundo. No sampling method was used. The lay midwives were recruited for participation by the MOH RNs who informed the lay midwives about the preeclampsia educational activity (See Educational Activity Box.) and the project a month beforehand. Upon arrival at the health clinic, the lay midwives were informed in detail about the study. They were advised that the preeclampsia education would not be withheld whether or not they chose to participate in the study; that willingness to complete the survey served as consent for study participation; and that they were free to leave at any time. Any participant who identified as a midwife and spoke Spanish or Kaqchikel was invited to participate. All information was provided in Spanish and translated into Kaqchikel.

Of the 11 lay midwives attending the educational activity, all agreed to participate in the-post evaluation project in 2021 and 2022. All questionnaires were completed; thus, no forms were discarded. To address the final aim of knowledge retention regarding obstetrical emergencies, nine midwives who had attended an educational activity in 2018, voluntarily completed an eight-item posttest in 2021.

Table 1 displays demographic information. Age range of participants was 30 to 75 years with an average of 53 years. Experience as a lay midwife ranged from one to 50 years with an average of 22 years. Formal education ranged from none to 15 years with an average of 6.35 years. Participants reported attending none to 13 births a month, for an average of four. Four participants could read, write, and count. Two could read and write. Two could write. Two could not read, write, or count. One could read. The groups consisted of 10 Spanish speakers and one Kaqchikel speaker. Other information asked included comfort transferring pregnant patients with obstetrical emergencies to hospitals. Three participants were comfortable, two were slightly comfortable, and three were slightly uncomfortable.

Data Collection

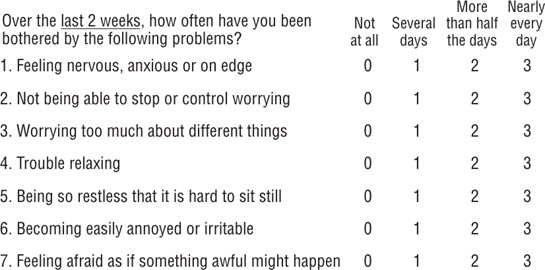

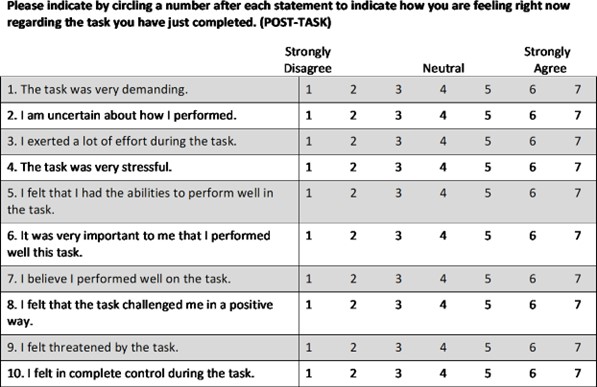

Data was collected face-to face on paper forms. RNs from the MOH and Refuge International volunteers assisted low-literacy lay midwives complete all forms. The questionnaire included two parts, a six-item demographic profile and a 17-item pretest/posttest questionnaire about preeclampsia knowledge. The 17-item questionnaire included 14 fill-in-the blank questions about normal blood pressure, high blood pressure, six signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, three actions to take if a patient has preeclampsia, and three results that can occur if the patient with preeclampsia doesn’t get needed medical attention. The 17-item questionnaire also included three questions about the correct way to take blood pressure. Two answers, one correct and one incorrect, were offered for these three questions. Participants were invited to circle the correct answer to each of these three questions. The six-item survey about obstetrical emergencies came from the HBLSS. (See Survey Boxes).

The PI, who has had a program of study since 2009 with Guatemalan lay midwives in partnership with the MOH and Refuge International, developed the demographic profile and surveys based on a literature review about Guatemalan lay midwives and obstetrical emergencies. A judge panel of three experts established face validity of the tools and a Fog Index of 0.35. The Fog Index measures the readability of the writing sample. The resulting score is an approximation of the number of years of formal education required to understand the tool on first reading. In other words, participants with less than a year of formal education should understand the questions on the demographic profile and the questionnaires.

Data Analysis

The evaluation relied on frequencies and measures of central tendency to analyze demographic data. Scores on the pretest and posttests were based on the total number of correct answers from a questionnaire about preeclampsia and obstetrical emergencies.

Results

The average preeclampsia pretest score was 5.36 out of 17 (31.52%). The average preeclampsia posttest score was 15 (88.23%). The average knowledge retention score about preeclampsia was 11.18 (66%). The average knowledge retention score about obstetrical emergencies was 4.4 (73.33%) compared to 51% on the pretest and 85.5% on the posttest. (See Results Box.)

Most participants had a simplistic understanding of preeclampsia. Before the educational activity, they knew what normal blood pressure was, that headaches and blurred vision were signs of preeclampsia, likely because these signs are taught in the MOH classes, and that they needed to transfer patients with high blood pressure to the hospital. However, most participants lacked a more in-depth comprehension of preeclampsia that could help them save lives,

After the educational activity, most participants knew what high blood pressure was. They could recite other signs and symptoms or preeclampsia, such as nausea and vomiting, right upper quadrant pain, and peripheral edema. They also understood they needed to place the patient on her left side, and that the patient could seize, and she and her fetus could die, if the patient did not receive medical treatment.

Information participants were most likely to forget was that hyper reflexes can be a sign of preeclampsia, and they shouldn’t put anything in the patient’s mouth. Further, lay midwives could recall the correct mechanics for taking a blood pressure, such as the patient should sit without her legs crossed, and she should have her feet on the ground. However, participants fumbled a bit with the mechanics of taking a blood pressure, which is normal when this skill is introduced.

In addition to the laminated Preeclampsia Reminder Cards, all participants were given a backpack with a stethoscope, sphygmomanometer and two birth kits that included blue pads to put under patients, exam gloves, umbilical cord clamps, scissors, razors, soap, iodine, bulb suctions, tape measures, and newborn onesies, and knitted baby hats and sweaters.

Participants were encouraged to continue practicing taking blood pressures with family members and friends at home. MOH RNs asked the lay midwives to bring blood pressure instruments to monthly meetings at the MOH so RNs could continue providing guidance on this skill. The PI also requested that participants keep data on the number of obstetrical emergencies they see to share during future studies to evaluate if the educational activities are changing lay midwife practice.

Regarding knowledge retention, participants retained more information about obstetrical emergencies (73%) than preeclampsia (66%), despite the time frame being longer between testing periods, four compared to one year, likely because MOH RNs frequently teach lay midwives about obstetrical emergencies. A closer timeframe for retesting about obstetrical emergencies was precluded by the COVID pandemic.

On a positive note, knowledge retention scores among lay midwives in San Raymundo were better than knowledge retention scores among rural lay midwives regarding PPH (Garcia & Dowling, 2018). In 2016, ten lay midwives from remote Sarstun retained 21% of eight steps to address PPH on a pretest and 65% of steps on a posttest after a second educational activity when evaluated seven years after an initial educational activity in 2009 (Garcia & Dowling, 2018). By comparison, twelve lay midwives, including ten from 2016, identified 17.5% of steps on a pretest and 60% of steps on a posttest to address PPH after an educational activity in 2009 (Garcia et al., 2012).

Ideally, Sarstun lay midwives should have been evaluated for knowledge retention at a closer interval that seven years. These lay midwives still had more knowledge about PPH in 2016 than they had before an initial educational activity in 2009. Further, Sarstun lay midwives likely had lower retention scores than San Raymundo lay midwives as Sarstun midwives were retested at a longer interval, and Sarstun lay midwives are less literate and live more remotely than San Raymundo lay midwives.

Discussion

Results from this study reinforce recommendations in the literature to provide information in the native language of participants, orally for low-literate audiences, with educational activities and drawings to reinforce knowledge retention, and to respect and integrate knowledge and practices from participants. Results from this study demonstrate that the knowledge of low-literacy participants will improve and be retained when these suggestions are followed.

Limitations of the study

This study took place during the COVID-19 global pandemic, which further alienated already marginalized groups, such as the indigenous. Thus, the sample size was smaller than ideal and may not be generalizable to lay midwives in urban Guatemala. Lay midwives who attended the study during COVID-19 were likely to be more affluent than most lay midwives, which could have led to sampling bias. Further, only one indigenous lay midwife participated in this educational activity compared to five indigenous among 17 lay midwives who participated in a 2018 educational activity about obstetrical emergencies. Finally, most lay midwives answered the questions correctly that had to be circled in the preeclampsia survey which may have led to question bias.

Conclusion

Clearly teaching low-literacy audiences who speak indigenous languages in Spanish with written material is not effective. Instead, low-literacy audiences learn best with educational activities, such as roll plays, repetition, storytelling, hands-on practice, and return demonstrations, presented orally in their native languages.

Knowledge retention cards about obstetrical emergencies, such as preeclampsia, should be created with cultural humility to increase visual literacy. Simple, color drawings from inside the culture are more effective than complex, black and white drawings from outside the culture. Evaluation of knowledge retention should occur yearly at the very least. Data should be consistently collected on lay midwife responses to obstetrical emergencies to evaluate if the educational activities are changing practice, and ultimately decreasing the MMR in Guatemala.

Ethical Aspects and Conflict of Interest

The study was conducted with the approval of the UU Internal Review Board. Issues of confidentiality and anonymity were addressed. The study encompassed has no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study did not receive a grant or funding from a public, commercial or non-profit source.

References

- American College of Nurse Midwives Division of Global Engagement. (2018). ACNM Global Health Competencies and Skills. Retrieved from https://www.midwife.org/acnm/files/cclibraryfiles/filename/000000007496/Global%20Health%20Competencies.pdf

- Bailey PE, Szászdi JA, Glover L. Obstetric complications: does training traditional birth attendants make a difference? Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002 Jan;11(1):15-23. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892002000100003. PMID: 11858126.

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2020). Central America: Guatemala. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/maternal-mortality-ratio/country-comparison

- Chae, SY, Chae, MH, Kandulas, S, Winter, RD. (2017). Promoting Improved Social Support and Quality of Life with CenteringPregnancy Group Model of Prenatal Care. Arches of Women’s Mental Health, 20(1) 209-220. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0698-1

- Chary A, Díaz AK, Henderson B, Rohloff P. The changing role of indigenous lay midwives in Guatemala: new frameworks for analysis. Midwifery. 2013 Aug;29(8):852-8. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.08.011. Epub 2013 Feb 12. PMID: 23410502.

- Every Mother Counts (2022). Guatemala: A Deeper Dive. Retrieved from https://everymothercounts.org/grants/guatemala-a-deeper-dive/

- Fahey, JO, Cohen, SR, Holme, F, Buttick, ES, Dettinger, JC, Keslter, E, Walker, DM. (2013). Promoting Cultural Humility During Labor and Birth. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 27(1), 36-42. http://DOI:10/1097/JPN.0b013e31827e478d

- Foster J, Anderson A, Houston J, Doe-Simkins M. A report of a midwifery model for training traditional midwives in Guatemala. Midwifery. 2004 Sep;20(3):217-25. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2004.01.004. PMID: 15337277.

- Garcia, K, Dowling D, Mettler, G. (2018). Teaching Guatemalan traditional birth attendants about obstetrical emergencies. Midwifery, 61, 36-38. https://doi.org.10.1016/j.midw.2018.02.012

- Garcia, K, Morrison, B, Savrin, C. (2012). Teaching Guatemalan Midwives about Postpartum Hemorrhage. MCN: American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 37, 42-47. http:// doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3182387c0a.

- Garcia, M, Chismark, EA, Mosby, T, Day, S. (2010). Development and Validation of Nutritional Educational Pamphlet for Low Literacy Pediatric Oncology Caregivers in Central American. Journal of Cancer Education, 25(4), 512-517. Doi:10.1007/s13187-010-0080-3

- Garcia, K. (2022). An Observational Study of Teaching Methods with Low-Literacy Comadronas in Urban Guatemala. Canadian Journal of Midwifery Research and Practice, Volume 21, Number 3.

- Goldman, N. Glei, D.A., Pebley, A.R., & Delgado. H (2001). Pregnancy Care in Rural Guatemala: Results from the Encuestra Guatemalteca de Salud Familiar. Rand. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/drafts/2008/DRU2642.pdf

- Greenberg L. Midwife training programs in highland Guatemala. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(18):1599-609. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90290-8. PMID: 7146937.

- Hernandez, S, Bastos Oliveria, J, Shitazian, T. (2017). How a Training Program is Transforming the Role of Traditional Birth Attendants from Cultural Practitioners to Unique Health-care Providers: A Community Case Study in Rural Guatemala. Frontiers in Public Health, 5(111), 1-8. http://doi.10.3389/fpubh2017/00111

- Hinojosa SZ. Authorizing tradition: vectors of contention in Highland Maya midwifery. Soc Sci Med. 2004 Aug;59(3):637-51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.011. PMID: 15144771.

- Juarez, M, Juarez, Y, Coyote, E, Nguyen, T, Shaw, C, Hall-Clifford, R, Gillard, G, Rohloff, P. (2010). Working with Guatemalan Lay Midwives to Improve the Detection of Neonatal Complications in Rural Guatemala. British Medical Journal Open Quality, 9(1), e000775. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000775

- Juarez M, Juarez Y, Coyote E, Nguyen T, Shaw C, Hall-Clifford R, Clifford G, Rohloff P. Working with lay midwives to improve the detection of neonatal complications in rural Guatemala. BMJ Open Qual. 2020 Jan 23;9(1):e000775. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000775. PMCID: PMC7011902.

- Kestler, E, Walker, D, Bonvecchio, A, Saenz de Tejada, S, Donner, A. (2013). A matched pair cluster randomized implementation trail to measure the effectiveness of an intervention package aiming to decrease perinatal mortality and increase institution-based obstetric care among indigenous women in Guatemala: a study protocol. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth, 13(73), 1-11. http://doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-73.

- Lang, JB, Elkin, ED. (1997). A study of the beliefs and birthing practices of traditional midwives in rural Guatemala. Journal of Nurse Midwifery, 42(1), 25-31.

- Maupin JN. Remaking the Guatemalan midwife: health care reform and midwifery training programs in Highland Guatemala. Med Anthropol. 2008 Oct-Dec;27(4):353-82. doi: 10.1080/01459740802427679. PMID: 18958785.

- Mosby, TT, Hernandez Romero, AL, Molina Linares, AC, Challinor, JM, Day, SW, Caniza, M. (2015). Testing efficacy of teaching food safety and identifying variables that affect learning in a low-literacy population. Journal of Cancer Education, 30 (1) 100-7.doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0666-2.

- Roost, M, Johnsdotter, S, Liljestrand, J, Essen, B. (2004). A qualitative study of conceptions and attitudes regarding maternal mortality among traditional birth attendants in rural Guatemala. British Journal of Obstetrical Gynaecology, 111, 1372-1377.

- Sibley, L, Tebben Buffington, S, Beck, D, Armuster, D. (2010). Home Based Life Saving Skills: Promoting Safe Motherhood Through Innovative Community-Based Interventions. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 46(4), 258-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1526-9523(01)00139-8

- Summer, A, Walker, D, Guendelman, S. (2019). A Review of the Forces Influencing Maternal Health Policies in Post-War Guatemala. World Medical and Health Policy, 11(1), 59-82. http://doi.10.1002/wmh3.292

- Thomas, S. B., Fine, M. J., & Ibrahim, S. A. (December, 2004). Health disparities: the importance of culture and health communication. American Journal of Public Health., 94(12): 2050. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2050

- Thompson LM, Levi AJ, Bly KC, Ha C, Keirns T. Premature or just small? Training Guatemalan birth attendants to weigh and assess gestational age of newborns: an analysis of outcomes. Health Care Women Int. 2014 Feb;35(2):216-31. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2013.829066. Epub 2013 Oct 18. PMID: 24138160; PMCID: PMC3925468.

- United States Agency for International Development (2017). Ending Preeclampsia: Focus Country Guatemala. Retrieved from https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/620/

- United States Agency for International Development (2022). Indigenous Peoples. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/guatemala/indigenous-peoples

- Walker, DM, Holme, F, Zelek, ST, Olvera-Garcia, M, Montoya-Rodriguez A, Fritz, J, Fahey, J, Lamadrid-Figueroa, H, Cohen, S, Kestler, E. (2015). A process evaluation of PRONTO simulation training for obstetric and neonatal emergency response teams in Guatemala. BMC Medical Education, 15(117), 1-8. http: doi: 10.1186/s/12909-015-041-7

- Walsh, L. (2006). Beliefs and Rituals in Traditional Birth Attendant Practice in Guatemala. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17(2), 148-154. http://DOI:10.1177/1043659605285412

- Weiss-Laxer, NS, Mello, MJ, Nolan, PA. (2009) Evaluating the education component of a hospital-based child passenger safety program. Journal of Trauma, 67. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a93512

- Weiss, HB, Bouffard, SM, Bridglall BL, Gordon, WE. (2009). Reframing Family Involvement in Education: Supporting Families to Support Educational Equity. Equity Matters, Research Review, No. 5.

- Zelter, N. (2018, December, 13) A Sacred Calling: Midwifery in Guatemala. Midwifery Around the World, 12/13/2018. https://medium.com/midwifery-around-the-world/a-sacred-calling-midwifery-in-guatemala-539768907dc7

Box: Educational Activity about Preeclampsia

The educational activity about preeclampsia began by asking lay midwives the following questions in a group format: what are the signs and symptoms of pre-eclampsia, what is normal blood pressure what is high blood pressure, what is the proper way to take a blood pressure, what should they do if a patient show signs of pre-eclampsia, what are the consequences of pre-eclampsia for the patient and fetus.

Information came from the group first and was provided if the group was lacking knowledge or provided incorrection information, in a Centering-Pregnancy style fashion, which improves participant engagement (Chae et al, 2017). Information was repeated back, multiple times throughout the educational activity. Lay midwives also participated in roll plays with an actor pretending to be a patient with pre-eclampsia and in return demonstrations of taking a correct blood pressure.

Participants practiced taking blood pressures on each other for an hour. Questions were asked during return demonstrations, such as should the patient cross her legs or have them flat on the ground? Should the patient be sitting, standing, or lying down? At what level should the arm be when taking a blood pressure.

Laminated, Preeclampsia Reminder Cards were given to participants to support knowledge retention of the signs, symptoms and interventions. The Reminder Cards were modified to improve visual literacy. Reminders for the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia came from MOH drawings of obstetrical emergencies. Reminders for interventions regarding preeclampsia came from the ACNM’s HBLSS curriculum.

Table One: Demographic Data, N=11

| Data | Range | Average |

| Age | 30-76 | 53 |

| Years as Lay Midwife | 1-50 | 22 |

| Years of Formal Education | 0-15 | 6.35 |

| Primary Language | 10 Spanish | 1 Kaqchikel |

| Number of Births per Month | 0-14 | 4 |

| Comfort with Hospital Transfers | 4 comfortable 2 slight comfortable 3 uncomfortable 4 slightly comfortable Literacy | |

| Literacy | 4 Read, write, count 2 Read, write 2 Write 2 Does not read, write, count 1 Reads |

Survey Box: Preeclampsia Pretest & Posttest

| Questions | Correct Answers | Pretest Score | Correct Score | Retention Score |

| What is normal blood pressure? | 120/80 | 8/11 | 11/11 | 11/11 |

| What is hypertension? | 140/90 | 1/11 | 10/11 | 8/11 |

| What is the correct way to take blood pressure? Circle the correct responses. | Patient should be seated or lying down. Patient should cross her legs or patient should not cross her legs. Patient’s legs should be on the floor or its not important where patient’s legs are. | 1/11 1/11 1/11 | 7/11 9/11 8/11 | 5/11 4/11 5/11 |

| What are six signs and symptoms of preeclampsia? | 6. headache 7. blurred vision 8. nausea & vomiting 9. right upper quadrant pain 10. swelling that’s worse in the morning 11. hyper reflexes | 10/11 10/11 4/11 5/11 1/11 3/11 0/11 | 11/11 11/11 9/11 8/11 9/11 8/11 3/11 | 11/11 10/11 4/11 3/11 5/11 6/11 1/11 |

| What three actions should be taken if a patient has preeclampsia? | 12. Put her on her left side 13. Don’t put anything in her mouth 14. Transfer her to the hospital | 0/11 0/11 11/11 | 10/11 6/11 11/11 | 6/11 3/11 11/11 |

| What three things can happen if a patient with preeclampsia doesn’t receive proper treatment? | 15. She can seize. 16. She can die. 17. Her baby can die. | 1/11 1/11 1/11 | 11/11 11/11 11/11 | 10/11 10/11 10/11 |

Survey Box: Correct Examples of Obstetrical Emergencies for Pretest & Posttest Example

| Answers | Pretest Score | Posttest score | Retention Score |

| Bleeding | 14/17 | 17/17 | 9/9 |

| Infection of uterus, breast, urinary tract | 6/17 | 14/17 | 3/9 |

| Preeclampsia | 5/17 | 12/27 | 4/9 |

| Birth Delay | 8/17 | 15/17 | 8/9 |

| Vaginal Infection or Malaria | 6/17 | 13/27 | 5/9 |

| Grand Multiparous Patient | 13/17 | 16/27 | 9/9 |

Knowledge Retention Results Box

| Teaching Content | Year | Pretest | Posttest | Knowledge Retention & Year |

| Preeclampsia | 2021 | 32% | 88% | 66% 2022 |

| Obstetrical Emergencies | 2018 | 51% | 85.5% | 73% 2022 |

| Postpartum Hemorrhage | 2009 | 21% | 65% | 60% 2016 |