Abstract

Working in the health care field requires a high level of individual training, largely focused on clinical skills. Additional training regarding interprofessional and interpersonal skills has gained an increased focus in recent years, with many institutions encouraging health professionals to engage in supplementary training programs to better develop leadership capacity. This study aims to assess the impact of one such program, the Relational Leadership Initiative (RLI) taught at the University of Utah. Through qualitative interviews with RLI participants, researchers learned the impact of the program and its teachings on the work and wellbeing of health professionals. Three major themes emerged including (1) creating psychological safety, (2) fostering a culture of feedback, and (3) learning about one’s communication style. As institutions and health executives encourage such trainings among their teams of health professionals, they can work closer together to improve the care of their patients and communities.

Introduction

Health professions training primarily focuses on clinical and didactic experiences deemed essential to patient care and producing positive outcomes. Over the last decade, we have witnessed increased value placed on imparting the “softer” skills within health professions programming and education, specifically, an emphasis on intrapersonal and interpersonal communication to bolster leadership capacity.1–3 Notably, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative lists “interprofessional communication practices” as one of their primary competency domains.4 These skills have been linked to improved patient outcomes; one study found that after providers underwent a communication training course, medication adherence, patient self-efficacy, and hypertension outcomes improved.5 As such, many health professionals often seek additional training to improve their team-based skills at different points in their careers for personal and professional development reasons. 6,7

Historically, leadership programming in health systems highlights sustainable growth strategies of individual providers and less on the team unit.8,9 In recent years, however, the need for team training has become increasingly noticed.2 As such, academic institutions and health care organizations have developed home-grown leadership programs and communication seminars for staff to encourage their teams to be more cohesive and high functioning.9,10

While team training and working cohesively together is often the focus, a critical and often neglected piece of such training is ensuring that a sense of psychological safety is embedded in the programming. Indeed, the growth of an individual on an interprofessional team hinges on a group or team’s ability to create a safe space for its members to flourish.11 Psychological safety, described by Amy Edmonson, is “a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking.”12 It is a necessary foundation when bringing together health care workers from different professions to care for patients and improve outcomes. The classic landscape of psychological safety and communication has notably shifted with the recent COVID-19 pandemic, amplifying the need for people to collaborate while maintaining the highest level of care for their patients.13,14 Given the growing prevalence and value of leadership training, there is a need to identify and address current programming to foster psychological safety on health care teams and capture its effects on patient outcomes in this novel health landscape.

Relational leadership, a theory that aims to bring together a cross-generational, interprofessional, diverse group of health professionals, was initially developed in 2015.15 Since then, programs push an incorporation of its evidence-based principles; in the health care space, a leader in the movement is the Relational Leadership Initiative (RLI). RLI began as a collaborative partnership between Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and Intend Health Strategies, a clinician-founded non-profit focusing on communication and quality outcomes.15 Its programming started in 2017 and evolved to emphasize the development of leadership and advocacy skills within the greater health community via a longitudinal learning seminary-style curriculum, emphasizing four domains – self-management, coaching and mentorship, leading change, and teamwork. Each content module is designed to contribute to the larger goal of helping health professionals create authentic connections and cultivate relationships, thus enhancing collaboration.15 In 2019, RLI expanded its partnerships to include the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Utah. The program enjoyed immediate success, championed by a team of interprofessional faculty and housed in Health Science Education. In the spirit of quality improvement, the RLI core team at the University of Utah endeavored to understand the reasons for the program’s appeal.

Methods

Conceptual Framework

This study is a qualitative analysis of how health professionals at the University of Utah implemented and responded to the RLI programming from Fall 2019 to Fall 2020, and which aspects they have been able to integrate into their respective health care teams. Seventeen interviews were performed and transcribed, and then analyzed using Strauss’ Grounded Theory as the framework.16

Study Design

Three independent cohorts of 20 to 30 participants participated in the RLI programming at the University of Utah in Fall 2019, Spring 2020 and Fall 2020. Participants within each cohort were contacted via email between 4 to 14 months after completing the program and were asked for their voluntary participation in a 30-minute interview to discuss their perception and application of the RLI course to date. Forty-two participants were contacted, and 17 live interviews were conducted over Zoom video conference software. To reduce study bias, some participants were excluded from interviews because they did not complete the entire program or because they were part of this or another analysis of the program. Others did not respond to the inquiry to participate.

The study utilized a guided narrative strategy to build on questions written by the national RLI group. See Supplement A for the complete interview guide. All interviews were recorded and transcribed for data analyses, then uploaded to Atlas.ti, a HIPAA-compliant qualitative software package, to analyze and create codes. Codes were identified, defined, and organized into themes following the parameters set by grounded theory.16 Dual coders were utilized to increase the rigor and reproducibility of results. Given the quality improvement nature of this study, it was deemed exempt by the University of Utah’s Institutional Review Board (IRB 00134146).

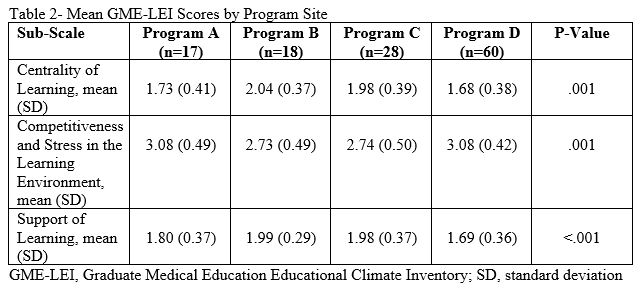

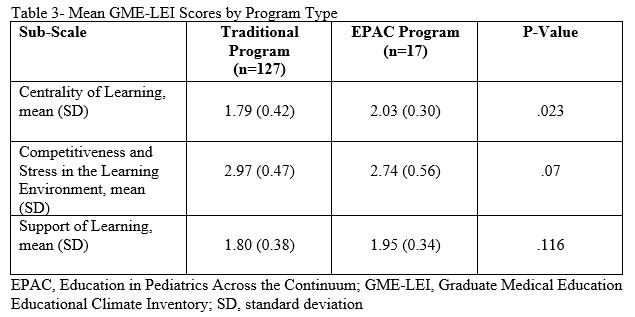

Results

Interview Themes and Responses

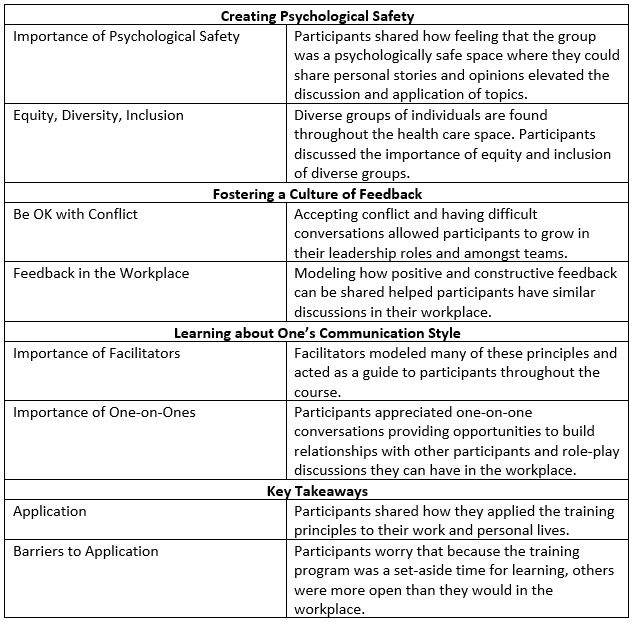

Three separate themes emerged from the interview topics, including the importance of (1) creating psychological safety, (2) fostering a culture of feedback, and (3) learning about one’s communication style.

- Creating Psychological Safety

“It is so different than what we are trained to do, especially in the health care profession. You never really talk about people’s lives outside of the home. You don’t ever really talk about your story. We so often just see each other in this one sphere of what we do.”

Psychological safety was a concept multiple participants appreciated and revisited throughout the training program.12 Psychological safety, centered around communicating in a safe space, is defined as the ability and insight to work together as individuals and as a collective group. For example, in discussing how to manage self-identity, the role of “teaming,” and communicating in conflict, participants found psychological safety to be the primary dictator of the success of small groups and even within the larger cohort. Participants shared how the RLI program modeled how a safe space is developed and expressed increased comfort in practicing difficult conversations. One participant shared how they “definitely felt very safe to be vulnerable in that setting, very supported by coparticipants and facilitators as well.” Others shared how setting group norms at the beginning of the training and revising the criteria to set expectations of how to work together, thus creating room for participants develop their own ideas of what would be discussed.

A necessary condition for psychological safety is the involvement individuals from multiple training backgrounds and subspecialties within health professions. Diversity within the group mirrors the interprofessional communities often seen in the health care setting. While reflecting on the training, one participant shared that “learning that everyone has a different background and different experience, and a different reality and perception of reality is something I knew I had a grasp of.”

- Fostering a Culture of Feedback

“Creating a culture of feedback was incredibly useful. I feel like that is what I want our culture to be like. People feel like they can engage and provide constructive criticism when needed or give people praise when needed.”

The integration of regular feedback into participants’ personal and professional lives is a critical aspect they will continue to apply going forward. Such conversations can be difficult, especially if it is contrary to the unit’s culture. However, as health care leaders learn to value feedback and feel more comfortable discussing feedback with colleagues, communication patterns can improve. Participants shared that through the program, they discovered “not to feel defensive about the feedback” and to be “more open to it, to try and look at [oneself] in a more honest way, trying to have a growth mindset.”

- Learning about One’s Communication Style

“I spent a lot of time watching how people facilitated, even though I was there to gain skills. I also was trying to learn and model off of them…that’s something I have become more self-aware of.”

Participants appreciated the facilitators, or group leaders, who modeled many of the concepts throughout the learning process before participants practiced them. Through facilitator modeling coaching and vulnerability, participants were allowed to feel safe to share stories themselves.

Another concept modeled was “one-on-ones,” or discussions between two individuals. Participants had the opportunity to role-play difficult conversations they may experience in the workplace, bringing their concerns to the RLI group. Role-playing helped participants work through problems and helped build relationships within the RLI cohort early on. For example, one shared that “one-on-ones helped me a lot…even if we didn’t solve the problems of the world, we could both relate to one another.”

The translation of these softer skills into the workplace was harder to replicate than initially anticipated. People came to the RLI training ready to learn and open themselves up to the training group; however, participants shared it was harder to model these things within their workplace.

Discussion

training program with a focus on relational leadership, they were able to broaden their perspective regarding psychological safety and learn together as a group. This study justifies the need for continuing education and training programs on topics of communication and teamwork. Interviews with RLI participants provide a wealth of knowledge regarding how the perspective of health care professionals changed post-program participation. Participation in leadership training programs helps health care workers broaden their perspective as they are exposed to different situations they may experience in practice. The study highlights how a program, such as RLI, may be central to this learning and shift in perspective while fostering a psychologically safe space.

Participants felt that the overall RLI programming helped them become more comfortable creating relationships on teams with diverse groups of people. In addition, the individual modules provided valuable opportunities to collaborate, practice difficult conversations, and flourish in their leadership abilities.

Research on teaching concepts of psychological safety to health professionals is often front-loaded in the initial clinical training; it is less often seen in continuing education or professional development courses after graduation.17 In this way, the RLI program presents a novel, interdisciplinary cohort-style learning experience, inviting health care professionals from diverse careers and statuses come together and discuss complex topics in the spirit of creating a psychologically safe space.

As health professionals work together in a psychologically safe space, with less of a hierarchical lens, initiative and creativity can be encouraged. Mistakes can be seen as opportunities to improve, and teams can work more closely together with patient safety as a primary focus.18

As increasing numbers of health care workers seek out supplementary leadership training, organizations should consider offering such programs. Similar to the results of this study, as health professionals participate in these programs, and improve their ability to communicate with other members of the interprofessional team, it is likely that they will be better equipped to work collaboratively on teams. As teamwork and leadership amongst health professionals improve, the level of care provided to patients will likely improve as well.19

Future opportunities for this research include a broader study involving participants from multiple sites at different follow-up times upon completion of the program. In addition, quantitative studies are concurrently underway that evaluate participant demographics, as well as their response to and application of the training.

Limitations

This study had multiple limitations. First, the sampling of individual participants came from one training location, the University of Utah, while the same program was conducted at other sites. Study subjects also participated in the program in multiple ways – some entirely in person, some a hybrid model of in-person and online, and others solely online due to restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews with previous participants may be susceptible to response bias, as those more satisfied with the program may have been more likely to respond to the interview request. Finally, the application of study results is limited to participants of studies similar to those described above.

This study’s strengths include the rigorous use of qualitative methods, including a semi-structured interview format and coding based on Strauss’ Grounded Theory.16 In addition, participants shared positive and negative feedback from the program, which will allow RLI leaders to adapt programming for future participants.

Conclusion

Through the integration of leadership training programs, like RLI, there is an opportunity for health executives and leaders to identify better ways to integrate teaming and leadership skills within their organizations to help their health professionals work together as they care for patients. This study offers a balanced perspective of positive and negative feedback from the program, which will allow RLI leaders to adapt the content for future participants. Most importantly, participants appreciated a psychologically safe space where they could experience self-growth and practice conversations they may have with others within health care or their patients. Such efforts open the door for health professionals to work more closely together in teams to improve the care of their patients and communities.

References

1. Back AL, Fromme EK, Meier DE. Training Clinicians with Communication Skills Needed to Match Medical Treatments to Patient Values. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S435-S441. doi:10.1111/jgs.15709

2. Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, et al. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221412. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0221412

3. van Diggele C, Burgess A, Roberts C, Mellis C. Leadership in healthcare education. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(Suppl 2):456. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02288-x

4. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Update. Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2016.

5. Tavakoly Sany SB, Behzhad F, Ferns G, Peyman N. Communication skills training for physicians improves health literacy and medical outcomes among patients with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):60. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-4901-8

6. Davila L. An Absense of Essential Skills in the Current Healthcare Landscape. Pharmacy Times.

7. Mata ÁN de S, de Azevedo KPM, Braga LP, et al. Training in communication skills for self-efficacy of health professionals: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):30. doi:10.1186/s12960-021-00574-3

8. Leggat SG. Effective healthcare teams require effective team members: defining teamwork competencies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):17. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-17

9. Zajac S, Woods A, Tannenbaum S, Salas E, Holladay CL. Overcoming Challenges to Teamwork in Healthcare: A Team Effectiveness Framework and Evidence-Based Guidance. Front Commun (Lausanne). 2021;6. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.606445

10. Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, et al. Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychol. 73(4):433-450. doi:10.1037/amp0000298

11. Appelbaum NP, Lockeman KS, Orr S, et al. Perceived influence of power distance, psychological safety, and team cohesion on team effectiveness. J Interprof Care. 34(1):20-26. doi:10.1080/13561820.2019.1633290

12. Edmondson A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(2):350-383. doi:10.2307/2666999

13. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety Among Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5893

14. Back A, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. Communication Skills in the Age of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):759-760. doi:10.7326/M20-1376

15. Relational Leadership Institute – Intend Health Strategies. Published 2022. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.intendhealth.org/strategy-pages/the-relational-leadership-institute-rli

16. Strauss AL, Glaser B. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Aldine de Gruyter; 1967.

17. Tsuei SHT, Lee D, Ho C, Regehr G, Nimmon L. Exploring the Construct of Psychological Safety in Medical Education. Acad Med. 2019;94(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S28-S35. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002897

18. Whitelaw S, Kalra A, van Spall HGC. Flattening the hierarchies in academic medicine: the importance of diversity in leadership, contribution, and thought. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):9-10. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz886

19. Babiker A, el Husseini M, al Nemri A, et al. Health care professional development: Working as a team to improve patient care. Sudan J Paediatr. 2014;14(2):9-16.

Coding and Themes from Participant Interviews

Appendix A: Interview Guide – Click here to view Interview Guide